Australia’s biggest financial institutions are in the spotlight, with ANZ Group Holdings (ASX:ANZ), Westpac (ASX:WBC), and National Australia Bank (ASX:NAB) posting half-year results, and Commonwealth Bank (ASX:CBA) delivering its third-quarter trading update. As lenders to all corners of the economy, the major banks give the best read-through on the nation’s financial health. Anyone investing in Australian equities can learn something from their results.

Here are our key takeaways.

Net interest margins stabilising at lower levels

Net interest margin, or NIM, is the difference between the rate at which banks borrow and lend. They borrow via deposits and wholesale markets and lend via home and business loans. By taking on this maturity mismatch, they earn a spread. The size of this spread is influenced by many factors, but the big ones are how aggressively banks need to set rates to win deposits and write loans.

Margins have been under pressure in recent years, squeezed by rising funding costs and intensifying competition. The expiry of the low-cost term funding facility, combined with customers switching from transaction to higher-rate savings and term deposits, has lifted interest expenses. Meanwhile, the growing dominance of mortgage brokers, who now account for 76% of new home loans, up from 52% in early 2020, is also eroding profitability, as banks pay commissions on broker-originated loans.

But margins appear to be finding a floor. ANZ’s NIM slipped just 2 basis points from the second half of fiscal 2024 to 1.56%, while Westpac’s fell 4 basis points to 1.92%. Meanwhile, NAB and CBA held margins steady. For CBA, we think its strategy of writing more loans directly is protecting margins, with just 32% of loans written via brokers in the March quarter, down from 46% in the December half. By comparison, 67% of Westpac’s loans were broker-originated in the six months to March.

Looking ahead, we expect NIMs to lift gradually as deposit competition eases, with non-major banks likely to scale back aggressive pricing to improve returns on equity. Falling cash rates should also see banks reduce discounts on new loans and offer less generous rates on deposits. But we expect only modest improvement from here, not a return to the margins the banks enjoyed before COVID.

Heavy, but necessary, investment cycle underway

The major banks are deep into multi-year investment programs focused on lifting efficiency, enhancing customer experience, and strengthening risk management. Execution risks look highest at Westpac and ANZ, given the scale and complexity of their respective transformation programs—Unite at Westpac and ANZ Plus at ANZ. But over time, we expect these investments to deliver meaningful benefits. Across the sector, we see scope for a material reduction in cost-to-income ratios as the banks simplify operations, digitise processes, and remove duplication.

Bad debts contained

Bad debts remain low across the banks, reflecting resilient household and business balance sheets. Home loan arrears are generally drifting higher across the majors—unsurprising given the higher interest rate environment—though this is off very low levels and remains well contained.

We think the banks are well provisioned for any near-term deterioration. Stress doesn’t appear widespread, though we expect arrears to edge up as tight monetary policy and lingering cost-of-living pressures weigh on the household sector.

CBA’s ROE remains well ahead of peers

If there’s one financial metric that matters most to bank investors, it’s probably return on equity. At the end of the day, the attractiveness of a bank—like any business—comes down to the returns it can generate on your capital.

We estimate the cost of equity for the major banks at 9%, reflecting a 4.5% risk-free rate and a 4.5% equity risk premium. A good bank should be earning at least this on new investments. Above it, the bank is creating value, and below it, destroying value.

So, how are the banks faring? In the first half, NAB generated an ROE of about 11%, and ANZ and Westpac about 10%. In each case, a fairly thin margin over our estimated cost of equity. CBA’s ROE for the six months ended December 2024 was almost 14%, comfortably above peers [Exhibit 1].

Exhibit 1: CBA better than peers, but the gap isn’t widening

Trailing twelve-month return on equity (smoothed)

Source: Company filings, Morningstar. Note: the big decline in major bank ROE in 2016 is a result of NAB’s Clydesdale impairment, while the 2021 reduction is mostly due to Westpac’s AUSTRAC fine.

CBA’s valuation looks stretched—better value elsewhere

All else equal, you’d pay more for a business generating higher returns on equity. But even the best business has a fair price, and CBA has long since surpassed it.

We know this might sound like a broken record. We’ve questioned CBA’s valuation before, and yet the shares keep climbing. Its latest result met expectations, offering little to unsettle investors. But what the market is willing to pay for those earnings remains, in our view, unjustifiable.

CBA now trades on 26 times forward earnings, with a dividend yield of just 3%. You can throw almost any bull case into a valuation model and still struggle to get to $170 per share.

It’s a high-quality franchise, no question. Its lower-cost deposit base, operating efficiency, and conservative underwriting relative to peers support superior returns, and justify a premium. But if we step back and look at ROE trends over the past decade, CBA hasn’t meaningfully pulled away from the other majors, yet investors are paying a much higher multiple than ever before, even as returns have drifted lower in line with the rest of the sector [Exhibit 2].

Exhibit 2: CBA’s huge valuation gap to peers

Trailing twelve-month price/book

Source: Company filings, Morningstar.

We understand investors might see it as the first port of call for Australian bank exposure, or even for general Australian market exposure. But let’s keep some perspective. The earnings outlook is not particularly inspiring. On our forecasts, CBA’s earnings are forecast to grow at an average of 5.5% during the next five years, a touch above nominal GDP. And if the banks are effectively a proxy for the Australian market, which has historically traded on about 15 times earnings, you have to ask why CBA—Australia’s biggest company—should trade on 26 times.

CBA has looked expensive for some time—and it has continued to defy gravity. We see more compelling opportunities elsewhere. Amongst the major banks, ANZ looks the most attractive, and we make the case in our earnings note on page 7.

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://d3k2r2mhaflwqi.cloudfront.net/wp-morningstar/20250404/67ef697cab05f63ce2195712/t_8c17ae9660684312b580719f61d0c059_name_250403_Malseed_Update/file_960x540-1600-v4.mp4?_=1Our US colleagues recently hosted a webinar where they discussed their updated economic and market outlooks. Naturally, investors over there were eager to understand how Morningstar incorporates such extreme economic uncertainty into its research, and they asked some thoughtful, probing questions.

I expect many of our Australian subscribers are wondering the same. So this week, inspired by the questions from our US clients, we’re turning the focus homeward to explore these issues through an Australian lens. I hope the answers will provide insight into our methodology and process, as well as what goes into our investment decisions.

How do macroeconomic events, like the recent tariff increases, factor into Morningstar’s equity ratings?

Our economic research team has downgraded its US growth forecasts and raised its inflation outlook in the wake of the tariff announcements. While our equity analysts consider these macro forecasts in their valuation work, there’s no mechanical link. We recognise that the short-term macroeconomic backdrop can be very important for certain industries, but long-term industry- and company-specific fundamentals are almost always more important drivers of our fair value estimates.

So, is your analysis of companies completely agnostic to tariffs?

No, it isn’t. Where tariff impacts are visible and significant, we incorporate them. But we need to keep things in perspective.

Let’s illustrate with a simple example: Breville (ASX:BRG), a manufacturer of kitchen appliances. Our fair value estimate for Breville—like our valuation for all companies we cover—is the sum of cash flows we expect the business to generate in the future, discounted to today. We discount these cash flows to account for the ‘time value of money’—the observation that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow.

As a manufacturer of appliances in China, Breville is unfavourably exposed to tariffs. About 40% of revenue is directly affected. Although price increases should offset some of the damage, we expect a hit to sales and margins in the short term. All up, we have reduced our fiscal 2026 operating earnings forecast by 5%.

But let’s put this into context. Breville‘s estimated cash flow for fiscal 2026 accounts for about 3% of our valuation for the business. In isolation, reducing this by 5% has a negligible impact on our fair value estimate.

The bigger question is whether Breville‘s earnings outlook is permanently impaired. If next year’s earnings account for 3% of our valuation, then the other 97% must be made up by fiscal 2027 and beyond. After all, stocks are perpetual securities, entitling investors to an infinite stream of cash flows if the business remains a going concern.

We believe a company’s long-run earnings potential is primarily determined by the durability of its competitive advantages, or economic moat. Eventually, competition should eat away at the excess returns of every business. But the longer a business can stave off this competition, the more we should be willing to pay for it, all else equal. For readers looking for a deeper dive, my colleague Mark LaMonica has put together a thorough discussion in his article ‘How to find a great company to buy’.

We don’t think Breville‘s moat has been impaired by Trump’s tariffs. It’s premium brand perception, and the pricing power this affords, remains. We also think the company can diversify its manufacturing away from China, which should limit the downside to earnings for as long as tariffs remain in place.

So, although we’ve cut near-term earnings, the isolated impact on our valuation is negligible. The long-run outlook is far more important—and we haven’t changed our view on this. So, our fair value estimate for Breville stands. The stock is down about 10% since April 2nd, and although it still looks overvalued, this severe reaction to tariffs is probably unwarranted.

Are Australian equities still overvalued after the tariff volatility?

It depends on how we look at it.

The Australian market remains expensive on a market-cap weighted basis, at a price/fair value ratio of 1.17—a 17% premium. But in a cap-weighted index, larger companies have considerably greater representation. Our blue chips, and especially banks, have looked overvalued for some time and continue to do so. CBA, which alone accounts for about 10% of the ASX 200, trades at a near 70% premium to fair value. Its shares have shrugged off the tariffs, up 8% since April 2nd.

But looking at the market on an equal-weighted basis—that is, giving each company, small or large, the same weighting in the index—our coverage trades at price/fair value of 0.98. It’s a slim 2% discount, and we’d consider this fairly-valued territory.

This was not so before the tariffs. At the start of 2025, our coverage traded at an equal-weighted premium of about 8%, so the selloff has uncovered many more opportunities, particularly at the smaller end of our coverage.

Have you incorporated greater uncertainty into your fair value estimates?

Some of our analysts, particularly in the US where the effects are most direct, have increased their Uncertainty Ratings on stocks. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’ve changed earnings forecasts, but we now need a wider margin of safety before classifying the stock as undervalued (4- or 5- star rated). This is done on an analyst-by-analyst and company-by-company basis. We are generally averse to making blanket changes to our Uncertainty Ratings.

Are we missing the forest for the trees here? These are not normal times. We are watching the US fall from a global economic leader to a self-isolated nation. Why wouldn’t we consider the impact of the recent actions from the US government in market valuations?

Though this question is not explicitly directed to the Australian market, some readers will own US stocks. And many ASX-listed companies own businesses in the US, so it’s important to consider whether we are witnessing ‘the end of US exceptionalism‘. Here’s our take.

We are indeed living in a period of uncertainty both in the US and from a global geopolitical perspective. But we believe that the US is still grounded in its constitutional framework and strong governing institutions.

While the system of checks and balances has been tested, we think it has withstood the test of time. Our very long-term outlook is still generally positive for the US from a macroeconomic and political standpoint because the US is still the world’s leading democracy; it has increased its gross domestic product at a steady pace for years; it still enjoys a unique leadership position in technologies of the future; and it maintains the world’s reserve currency, all of which contribute to macroeconomic stability.

Specifically, considering the impact of recent actions from the US government on market valuations, we’d make the following observations: First, it’s important to distinguish between statements, press releases, and tweets versus enacted policy; second, when policies are enacted, it’s essential to consider the effects, and we do. In this case, it appears that we are still in the early stages of enacting actual policy, with many countries approaching the negotiating table.

When discussing ‘longer-term intrinsic value,’ what is your definition of ‘long-term‘?

Our discounted cash flow valuation model incorporates a long-term forecast in three stages.

Stage one, our explicit forecast period, ranges from five to 10 years.

The length of the stage two forecast period can vary; it is estimated by each analyst seeking to model, for each company, a period over which returns on newly invested capital gradually and linearly revert toward the company’s weighted average cost of capital. This can range from zero to 15 years. Companies with wider moats have a longer stage two forecast period, reflecting our assumption that they can generate excess returns longer than less-moaty businesses.

Stage three of the model represents a perpetuity value, where excess returns on new invested capital are zero.

We typically expect that share prices will revert to our fair value assessment within three years, on average. Sometimes, the reversion period is longer than three years, and sometimes less than three years.

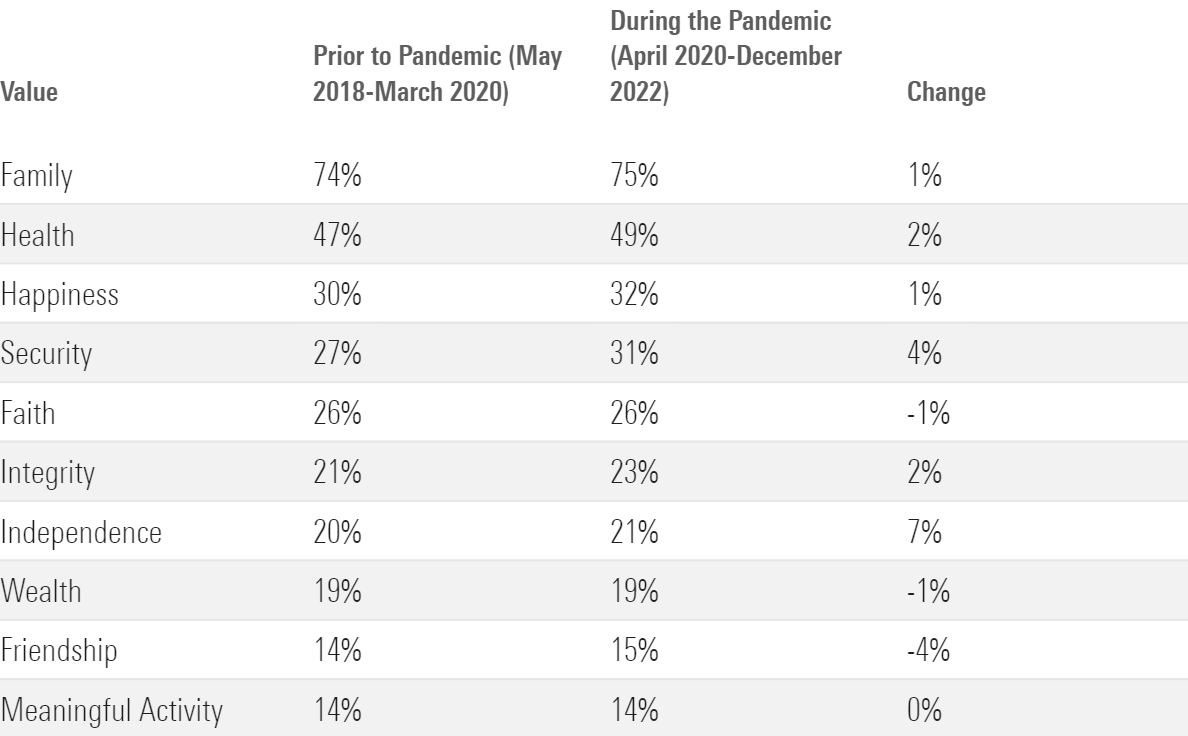

Advisers want their clients to have good financial habits—but like any good habit, financial ones are not so easy to build. Good financial behaviors are particularly difficult to build because of their repetitiveness and because their results can take months, years, or even decades to come to fruition.

However, many people still succeed in doing so. So, why do some struggle to build good financial habits while others don’t?

Conversations about good financial habits often go hand-in-hand with financial wellness—which encompasses both the objective ability to meet current and future financial needs as well as the subjective feelings of being financially secure and able to enjoy life. Although good financial habits are typically seen as a precursor to financial wellness, the truth may be more like a feedback loop wherein good financial habits promote financial wellness which, in turn, encourage more good financial habits.

Take the habit of building your emergency savings. Saving for an emergency is regarded as foundational, scales based on income, and is protective against financial shocks, yet many people struggle to do so. Both objective and subjective financial wellness may help people build an emergency saving habit. For example, people who are objectively well financially may already have some positive financial behaviors like saving for retirement and thus may find it easier to save for an emergency because they already have the skills and knowledge on how to put aside (and leave be) money every month. Furthermore, people who are satisfied with their current financial situation may be inspired to do things like save for an emergency not only because they don’t currently feel financial strain but also because they want to safeguard their financial satisfaction against an unknown future.

Given this, in our recent research, we explored how financial wellness may influence emergency saving behavior.

The more we understand the link between financial wellness and the ability to build better financial habits, the better advisers can leverage clients’ mindsets and actions to help them make better decisions.

The Link Between Financial Wellness and Emergency Savings Behavior

In our study, we surveyed 786 higher-income individuals (from households making a minimum of $100,000 annually). We examined the relationship between these individuals’ investable assets, current financial wellness (that is, how satisfied they are with their present finances), and their progress toward an adequately funded emergency savings (defined here as half of three months’ salary).

Overall, only 41% of our sample had achieved emergency savings adequacy.

So, why do so many higher-income individuals not hold proper emergency savings? We found that strong emergency savings was linked to both objective and subjective financial wellness.

That is, those who were dissatisfied with their finances (either objectively or subjectively) were less likely to have good emergency savings behavior. This was even more the case when a person had lower investable assets.

Breakdown of Emergency Savings Adequacy by Objective and Subjective Measures of Financial Wellness

However, financial wellness is not enough to wholly explain why some people did not save for an emergency. Even 30% of our most “well-off” (those who both felt satisfied with their finances and had higher than average investable assets) had not saved for an emergency. This demonstrates how easy it is to neglect this habit.

Furthermore, those who had not saved for an emergency showed signs of needing help to form the habit. Most of this group had less than half of an adequate emergency savings fund in place, and 26% of them didn’t have anything saved at all.

What we see is that although financial wellness is linked to emergency saving behaviors, advisers would be remiss to assume that a client who is doing well with their finances in one sense also has good behavioral habits. That is, someone may be ahead of the game when it comes to saving and investing in retirement but still have nothing saved in the event of an emergency.

However, in seeing this connection between objective and subjective financial wellness and emergency saving behavior, we do uncover insight into how to help those clients who need to build better habits.

How Advisers Can Help Their Clients Build Better Habits

To help clients, advisers should focus on supporting clients’ emergency saving behavior by addressing both their actions and their mindset. Although we focus specifically here on emergency saving behavior, much of this advice is relevant to any good financial habit you’d want a client to build.

- Promote financial self-efficacy. Financial self-efficacy is a person’s confidence in their own ability to manage their finances. Although it might sound odd for an advisor to promote this, it’s key for clients to feel confident about their ability to follow their financial plan to reap the rewards of working with an advisor. To that end, you should ensure that when you help your client build their habits, you are meeting them where they’re at. If your client only has the bandwidth to deal with one behavior change at a time, don’t foist more on them. As your client gains confidence, you can ratchet up the skills and habits you encourage in your client.

- Help your clients define what they are working toward. Not having a clear target to work toward can often prevent us from starting at all. Educate your clients on what their emergency savings should be, but don’t just give them an endpoint number. Help them calculate how much they can reasonably set aside each month and how long it will take to achieve their goal. Financial advisers are well-suited to help clients define these numbers given their understanding of not only finances in general but also the circumstances of a client’s finances.

- Create a step-by-step plan for execution. Although your clients might feel empowered after you help them crunch numbers in the first step, behavioral science research finds people often fail on the follow-through. However, you can help your client create a plan on how to enact these changes, which can help close the gap between wanting to do something and actually doing it. For example, if your clients are going to automate their saving, what steps do they need to get that done? Where will they keep the reserves, and what steps do they need to take to get it there? Helping your clients have a step-by-step plan can give them a leg up on the follow-through.

Altogether, advisers should remember that helping clients with their objective actions and their subjective mindset can help them build better habits like saving for an emergency.

Every generation demands something different of financial advisers. Next-gen investors are often defined by their relationship to technology, which provides both challenges and opportunities for advisers to meet clients where they are and to address unique needs technology can’t.

There’s no doubt younger investors’ attitudes toward investing are coloured by technology. They’ve grown up with quick access to an abundance of information that artificial intelligence now makes easier to process and digest—meaning, they feel more comfortable finding and vetting financial information themselves than previous generations. They’re also comfortable interacting with low-cost trading platforms. As a result, younger investors often manage the transactional side of investing on their own and build investing confidence, experience, and knowledge through experiential learning like interactive portfolio stimulations.

Yet, a little knowledge can be dangerous; confirmation bias increases at the early stages of learning, as we draw assumptions based on incomplete information. Similarly, other cognitive biases like overconfidence and the availability heuristic can lead to a miscalibration of risk and return and unrealistic expectations. Further, investors may develop a warped view of their finances (money dysmorphia) from comparing their situations with what they see online.

As a result, the latest generation of investors may feel that they need less guidance with their finances than their parents did at the same stage of life, while at the same time requiring more guidance to meet their expectations of investing.

How advisers can engage the next generation of clients

- Challenge: Younger investors want to be active in their financial journey and view consumption as an expression of individual identity. As a result, they expect advisers to work with them to tailortheir financial plans.

Opportunity: Be a financial co-pilot. Invite your younger clients to participate in the planning process by helping them articulate their goals and expectations and working together to build their plan. This fulfills their need for ownership and individuality in their financial plan and positions the adviser as an invaluable collaborator.

- Challenge: An on-demand culture means advisers are competing against short-form and often free sources of financial knowledge. The newest generation of investors may not readily see the benefit of a financial adviser’s advice when they are used to short, sharp, and affordable content they can access from their phones whenever they want.

Opportunity: Create bite-size services. Virtual and on-demand sessions and workshops can help expand your reach to younger audiences. You can also offer segmented services around goal discovery, cash flow management, portfolio building, and behavioral coaching. Though small, these offerings can sow the seeds with investors who are still building wealth and grow into a long-term relationship.

- Challenge: Younger generations of investors may place a greater focus on purpose and missionwhen it comes to their financial decisions. This means they may be less inclined to engage with financial advisers who are unclear about how personal values fit into financial planning.

Opportunity: Engage a values-driven approach. Advisers can help younger clients uncover personal values and craft meaningful goals that align with those values. This valuable service fosters deeper connections and results in meaningful strategies that better align with client preferences. As an added benefit, talking about nonfinancial concerns is an experience clients often share with their social circle, providing a valuable opportunity for advisers to reach new audiences.

All three strategies can serve as a sticky entry into financial advising by filling the needs of next-gen investors that cannot be met with just Google and ChatGPT.

The current crisis has divided investors and commentators largely into two camps:

The bull camp – The bulls see Trump backing down from his extreme tariff demands and carrying out ‘the art of the deal’ with friend and foes. Though there might be a brief economic impact, inflation won’t spike, interest rates will come down, and that will spur economic growth and a renewed bull market in equities, the bulls believe.

The bear camp – The bears see an imminent US and global recession and stock markets not yet adapting to that reality. Even if Trump backs down from the large tariffs in place, it won’t be enough to prevent the shock that’s coming. And the bears think it mightn’t be a short and sharp downturn either, as moving away from globalisation will do long term damage to global growth and corporate margins and earnings.

The truth probably lies somewhere between these two extremes, though it’s impossible to tell.

Economists tell us with certainty that tariffs are always bad news and point to the 1930 Smoot-Hawley legislation that supposedly caused the Great Depression. The problem is that it didn’t cause the Depression and there’s genuine debate about how much it contributed to the depth and length of the depression that took place. The same economists also don’t talk about how the US and many other countries thrived in the second half of the 19th century when tariffs were consistently very high.

Some historians find Trump’s tariffs analogous to the Nixon shock of 1971 when the then US President took the dollar off the gold standard, implemented a 10 per cent import tariff, and introduced temporary price controls.

Others find parallels between Trump and China’s famous post-World War Two leader, Mao Zedong. Mao celebrated conflict and ‘permanent revolution’. His ‘Great Leap Forward’ to collective agriculture in 1957 resulted in more than 30 million deaths from starvation and famine-related illness. And later, in the 1960s, he launched a ‘Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution’ to fight bureaucratic resistance (the deep state) to his absolute power.

The problem with these views is that they try to find patterns from the past to make sense of the present and to forecast the future. The reality is that economies are infinitely complex and it’s difficult to determine the future with certainty. Also, though history makes for great stories and reading, the past is always different from current circumstances. Today’s world is nothing like the 1930s or the 1970s.

4 types of investors in crises

Because bear markets bring heightened uncertainty and emotion, investors often act in less than rational ways, and this downturn has been no different. Broadly, investors in crises fit into four categories:

The panickers. These investors sell out at the first sign of market trouble. It might be because they are young or novice investors. Or they’ve speculated and are horrified at the losses that they are enduring. Or they’ve read all the negative news and taken it to heart.

The buy the defensives. These investors switch from growth stocks to defensive shares, as well as bonds and cash, after the market has melted down. You can look at the amount of money going into Woolworth and Coles of late to see this phenomenon in action.

The buy the dippers. Ah, there are plenty of these investors! They’ve used the recent market turmoil to top up existing positions or buy new ones, because ‘the market is down 15% (or whatever it is) and that is an opportunity to buy’. Problems arise when these investors buy stocks just because prices are down. There’s a big difference between price and value, and just because a company’s shares have gone down in price, it doesn’t necessarily make them great value.

The procrastinators. These are the investors that are waiting for the bottom in markets ie. the ‘perfect time’ to buy stocks. The issue is that the market never announces when that time comes, and often these investors freeze and end up never buying, while consoling themselves that another time in future will be the ‘perfect time’ to invest.

What do these investors have in common? They’re generally not long-term investors and they don’t have a financial plan.

The benefit of being long term and having a plan is that you’re less likely to make rash decisions when crises happen. You’ll have the building blocks in place that you’ll largely be able to ignore what the market is doing.

As the late John Bogle said:

“My rule — and it’s good only about 99% of the time, so I have to be careful here — when these crises come along, the best rule you can possible follow is not “Don’t stand there, do something,” but “Don’t do something, stand there!”

Strategies to take advantage of this market meltdown

That said, there are tweaks that you can make to take advantage of market corrections and bear markets. Here are four ideas:

1. Rebalance or overbalance your portfolio.

This is an obvious one. If your 60/40 equities/bond portfolio has become 50/50, it makes sense to increase the equities allocation back to 60%.

A strategy for those who want to get a little more aggressive without going ‘all in’ on the market is to overbalance the portfolio. This means that instead of just rebalancing the portfolio from 50/50 back to 60/40 stocks/bonds, you could instead go 65/35 stock/bonds in anticipation of better long-term performance from equities given the lower prices on offer.

2. Buy listed investment companies at NAV discounts.

At times of market stress, LICs typically get whacked. First because of portfolio drawdowns. Second, because they trade at sometimes extreme discounts to their net asset values (NAVs). The current crisis is no different, and many good LICs are trading at +10% discounts to NAV, with some closer to 20%.

When markets eventually recover, you can benefit from increases to NAVs as well as a narrowing of the price discounts to NAVs (or they could trade at premiums).

3. Buy coiled-spring stocks.

While many investors hide out in defensive stocks and assets, a better strategy is to buy quality companies in cyclically challenged sectors. Think of retailers in Australia that are getting priced for the possibility of softer economic growth. Or stocks with US exposure like Aristocrat, where investors are thinking that the consumer there may soon be in trouble.

Source: Morningstar

4. Buying bombed out sectors.

The old saying is to buy when there’s blood in the streets. This requires guts and skill and is not for the faint hearted.

One sector that’s undoubtedly bombed out right now is oil and gas. Like in 2020, this sector is completely unloved, and yet the fundamentals of supply and demand don’t look as bad as current prices suggest.

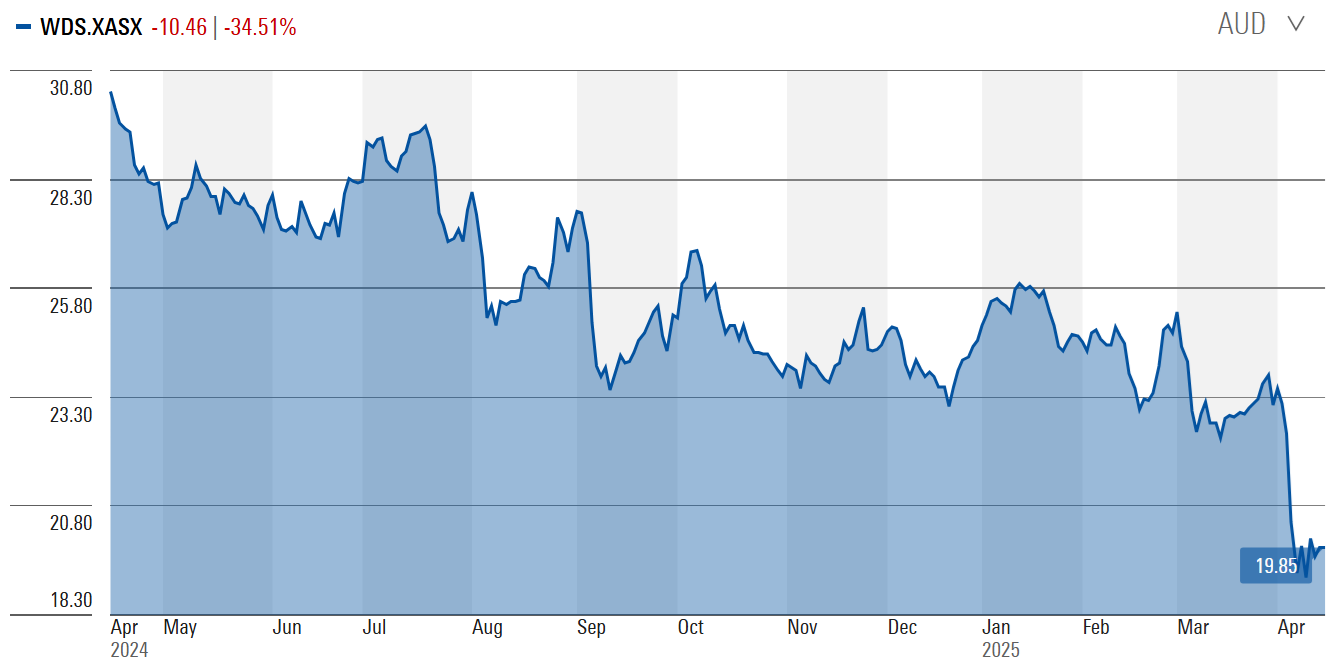

Woodside share price

Source: Morningstar

We rarely see selloffs like the one that followed “liberation day”. April 3rd and 4th marked the worst two-day stretch for US equities since the pandemic. It’s exceeded by only a handful of events in the past century: Covid, the GFC, the 1987 crash, and the Great Depression. When even gold doesn’t look safe enough—it too was falling at the peak of the meltdown—you know the market is in full-blown panic.

Exhibit 1: Liberation day ranks amongst the worst selloffs on record

S&P 500 2-day price return

Source: Macrobond, Morningstar.

Howard Marks, cofounder of Oaktree Capital and an investor always worth listening to, released his latest memo, Nobody Knows (Yet Again), on 9 April. The title echoes a note he penned during the darkest days of the 2008 financial crisis, just after Lehman Brothers—a Wall Street titan—shocked the world by filing for bankruptcy. That collapse triggered a wave of failures and raised fears that the entire financial system might unravel. It felt like a “downward spiral without end”. No one knew whether it could be stopped. But in Marks’ view, we had to assume it would be.

Of course, he was right. Central banks and fiscal policy stepped in, stabilized the financial system, and markets eventually recovered. It was a painful shake out, but a finite one. And I think that’s the position we must take today. We don’t know how it all plays out—nobody does—but we’ve faced big shocks in the past. And while there’s been pain along the way, in the long-run, markets have recovered.

If we’re willing to assume this, then we should be looking for opportunities in these moments. Some investors just want cash and they’re willing to liquidate at almost any price, and that’s where rational investors can take advantage. As Buffett puts it “the stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient”.

Marks concluded his latest memo in much the same way he did in 2008. I’ll quote in full:

“Everyone was happy to buy 18-24-36 months ago, when the horizon was cloudless and asset prices were sky-high. Now, with heretofore unimaginable risks on the table and priced in, it’s appropriate to sniff around for bargains: the babies that are being thrown out with the bath water. We’re on the case.”

In the spirit of Marks’ memo, let’s pick out a few babies from our Australian stock coverage.

Spotting attractive investments

First, how do we identify opportunities? It begins with our proprietary star rating system. We rate all stocks we cover on a scale from 1 to 5. Stocks we assign 1- and 2-star ratings are overvalued, in our opinion. If investors buy overvalued stocks, we expect they will earn a less-than-fair return. For context, we assume a ‘fair’ return for the average stock on the ASX is 9% per year, comprising both dividends and price appreciation.

We consider 3-star stocks fairly valued. Of course, we don’t know a business’s intrinsic value to the nearest cent, so we put a range around our estimates. We adjust this band based on the confidence we have in our forecasts – the predictability of cash flows, the chance of material value destruction, and so on. For a stock of ‘medium’ uncertainty, we set the band 10% either side of our fair value estimate. If shares trade in this range, it’s a 3-star stock.

Finally, and this is where things get interesting for investors, we have 4- and 5-star stocks. These are the most attractive on valuation grounds. For whatever reason—perhaps earnings are cyclically weak, or the sector is out of favour—the market underappreciates the long-run cash-generation potential of these businesses. But ultimately, fundamentals dictate stock prices, and the market should converge to fair value. If you can buy a stock when it’s undervalued, and hold on, we think you’ll be rewarded with a better-than-fair return.

The “Babies” thrown out with the bathwater

The big selloff means many stocks we cover are undervalued. In fact, more than half our list is 4- or 5-star rated, well above average. There are plenty of high-quality companies that looked undervalued before liberation day, and now, the discount is even larger. Our Best Ideas list is the place to go for these picks.

For this exercise, I’m narrowing in on a specific class of stocks: high-quality businesses that you couldn’t get at a discount before liberation day, but now screen as attractive. These are the babies thrown out with the bathwater—caught up in indiscriminate panic selling despite strong fundamentals. To identify them, I’m filtering for companies that were rated 1-, 2-, or 3-stars before liberation day but have since dropped into 4- or 5-star territory. We’ll give preference to businesses with economic moats.

Here are the picks.

BHP Group

BHP Group (ASX:BHP) shares have fallen 5% since liberation day. It’s easy to read Mr Market’s mind on this one. As the world’s largest iron ore miner, BHP is leveraged to China’s steel production and economic growth. If, as many surmise, tariffs put further pressure on China’s slowing economy, this is bad news for iron ore demand. Copper operations offer some commodity diversification but demand for the red metal is still very much tied to China, mostly in manufacturing and industrial uses.

Not since the depths of the pandemic has our biggest miner looked genuinely undervalued. The post-pandemic commodity price boom lit a fire under BHP shares, sending them well above our estimate of fair value. But for the first time in years, we believe the balance of risk and reward has shifted in investors’ favour.

That’s not to say we’re bullish on the outlook for iron ore. We expect Chinese steel production to fall gradually over the next decade, reflecting demographic drag, slower urbanisation, and diminishing returns on infrastructure spending. But every asset, even those facing structural decline, has a fair price. And today, we think the market is too pessimistic on BHP’s long-run earnings outlook.

While we don’t award BHP a moat, it is a high-quality iron ore miner. Its Pilbara iron ore mines have long lives, with cash costs in or around the lowest quartile of the cost curve.

ANZ Group

As a bellwether for Australia’s economy and equity market, ANZ Group (ASX:ANZ) shares are down 6% since liberation day. Amongst the major banks, ANZ has been the weakest performer of the past 12 months, with shares weighed down by the bond trading scandal and the costs of the Suncorp (ASX:SUN) integration. It’s now a four-star stock, and the only major bank at a discount.

We think the market is underestimating ANZ’s earnings resilience and overreacting to near-term uncertainties. While execution risks remain, they are now well known and largely priced in. Meanwhile, process investments and a new core banking platform should improve ANZ’s competitive position in home lending, where it has recently underperformed relative to peers. These investments may take time to bear fruit, but they set the stage for improved operating efficiency, higher returns on equity, and more durable earnings growth.

Crucially, ANZ still benefits from the structural advantages that underpin the major banks’ wide moats: a sticky deposit base, strong capital buffers, and a dominant position in a highly regulated market. A fully franked dividend yield above 5% also looks attractive, especially compared to more expensive peers like CBA.

Ansell

Of all Australian healthcare names we cover, Ansell (ASX:ANN) looks most directly exposed to tariffs. Shares have been hammered, down 15% since 2 April. We can understand the knee-jerk reaction: roughly half Ansell’s earnings come from the sale of protective gloves in North America, most of which are manufactured in Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. These three countries were hit with some of the most punitive tariff hikes, averaging 35%. And although this has since been wound back to 10%, the suspension is only due to last 90 days.

But this is where Ansell’s competitive advantages come into play. A narrow-moat business, Ansell owns several of the largest and most reputable protective glove brands. In highly skilled industries, where the right brand is the difference between being protected from injury or not, and quality and fit matter, it’s hard for new entrants to chip away at incumbents like Ansell. When safety or employee satisfaction is at stake, there is little incentive to switch manufacturers to save a sliver of the cost base.

Ansell plans to immediately and fully pass on the cost of tariffs to customers. We think it has the pricing power to do so. Most competitors also source from Southeast Asia, so Ansell is not at a relative cost disadvantage. We forecast modestly softer demand from price increases, but it’s essentially immaterial. Shares now trade in 4-star territory.

IRESS

It’s not immediately obvious why IRESS (ASX:IRE) has underperformed since liberation day. Perhaps it has been caught up in the broad-stroke bearishness surrounding the technology sector. Or perhaps, as a provider of software to wealth managers and stockbrokers, the market is concerned about the financial health of its customer base.

Regardless of the rationale, we believe the selloff is unwarranted. Iress is a narrow-moat business with entrenched market share, particularly in Australian wealth management, where it services around two-thirds of the market by volume. Its products are deeply embedded in client workflows, giving rise to high switching costs, especially in regulated environments where consistency, compliance, and integration matter.

The company has cleaned house. Noncore assets have been sold, the balance sheet has materially improved, and dividends have been reinstated. Capital expenditure, while tracking above our prior expectations, is long overdue following years of underinvestment. These funds are being directed toward tangible growth initiatives, including digital advice tools and expanded cross-sell modules, which should enhance product utility and client retention.

In our view, the market is too focused on short-term expenditure and overlooking the improving fundamentals, recurring revenue base, and strategic positioning of the business. At current prices, we think the upside outweighs the risk.

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://video.morningstar.com/aus/hd/2025/250319_ARC_Webinar_hd.mp4?_=2I’ve been getting many questions from income investors about what to do with their money now that term deposit rates are falling, and bank hybrids are being phased out.

Here I’m going to run through the various options, and their pluses and minuses.

Term deposits

With the RBA cutting interest rates last month and potentially more cuts on the way, it seems the days of +5% fixed term deposit rates are largely behind us.

The biggest bank, CBA, has 12-month deposit rates of 4.2%, with 6- and 3-month rates at up to 3.4% and 3% respectively. It has a current ‘special offer’ of 4.6% for a 10-month deposit.

My favoured term deposit institution, Judo Bank, offers higher rates than CBA, at up to 4.85% for 3 months, and 4.7% for 12 months.

There are others that are also more competitive than CBA, such as UBank, ING, and Macquarie, though all come with conditions attached ie. spending and saving certain amounts to qualify for higher rates.

The current term deposit rates still seem a reasonable proposition given they remain well above the official inflation rate of 2.4%.

Cash ETFs are an alternative for those investors who don’t want to be locked into three-month plus term deposits. These ETFs invest in cash products and deposit accounts that are offered by reputable banks with distributions (ie. interest payments) that are typically paid out on a monthly basis.

The most popular cash ETF is Betashares Australian High Interest Cash ETF (ASX:AAA). It offers a current interest rate of 4.18%.

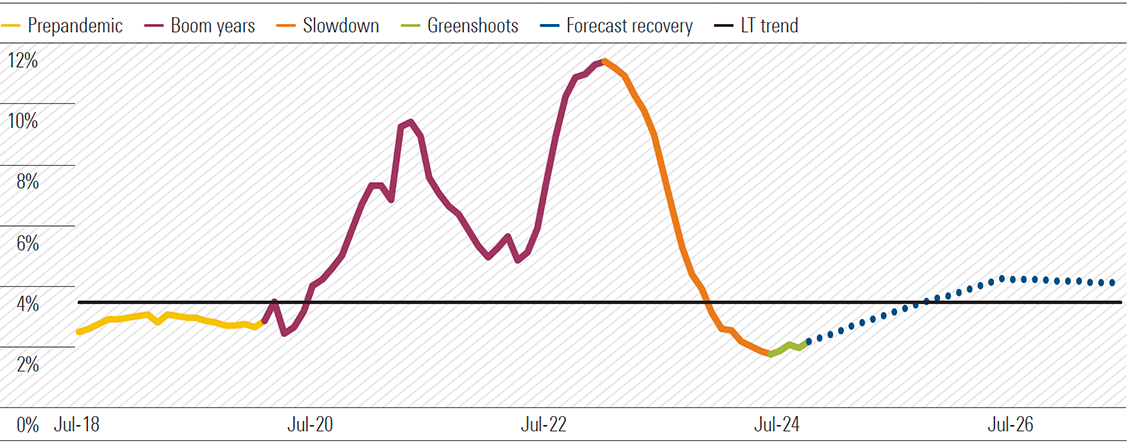

Government bonds

Government bonds have been in the doghouse for four years now. Despite the more attractive yields on offer, both institutional and retail investors have been reluctant to wade back into bonds.

Australian 10-year Government bond yields peaked above 4.8% in October last year and now sit at 4.46%.

Figure 1: Australia 10-year Government bond yield

Source: Trading economics

That yield seems ok given the circumstances. Unlike cash and term deposits, bonds offer protection for investors in the event of a slowing economy or recession.

The risk with bonds is if inflation ticks up again.

I’ve previously been vocal in suggesting that bond cycles usually last decades not years, and that the current bear market in bonds is likely to continue for some time. That said, Government bonds do still have a role to play in income portfolios.

You can buy Government bonds directly or via ETFs, the most popular being iShares Core Composite Bond (ASX:IAF) and Vanguard’s Australian Fixed Interest ETF (ASX:VAF).

Subordinated bonds

With hybrids being phased out from 2027, banks and issuers are likely to replace hybrids with other forms of capital like subordinated debt.

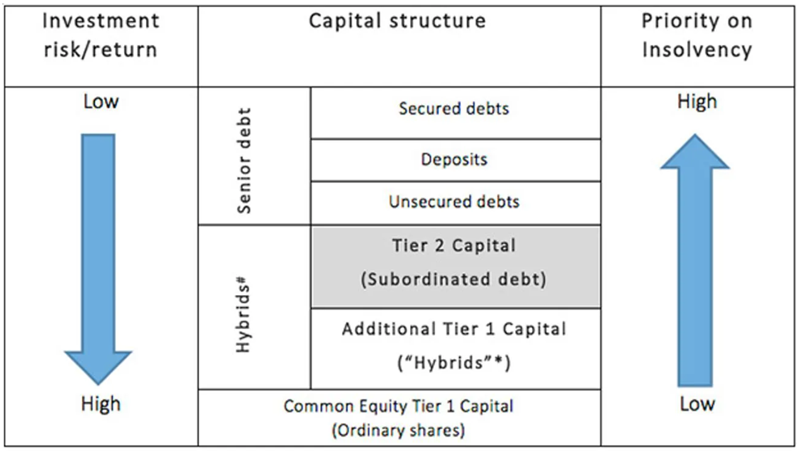

For context, there are different levels of debt in companies. The lowest risk is senior secured bonds, followed by senior unsecured bonds, and then subordinated bonds, otherwise known as junior bonds or lower Tier 2 debt.

Banks and insurance companies issue subordinated debt and Tier 1 hybrids as regulatory capital instruments. Their principal purpose is not as a source of funding but rather to add to the capital position of a bank or insurance company which can be used to absorb losses in a crisis scenario. These securities add to capital ratios that are monitored by regulators as an indication of risk.

Figure 2: Simplified capital structure of a financial institution

Source: ASIC

Betashares offers an Australian Major Bank Subordinated Debt ETF (ASX:BSUB) that has a current running yield above 6%. And Macquarie has just launched a Subordinated Debt Active ETF (ASX:MQSD).

The yields on subordinated debt are very reasonable, particularly given the quality of the major banks and insurers issuing the debt.

Hybrids

Hybrids are part equity and part debt instruments. They’ve been exceedingly popular with both banks and investors.

But with hybrids slowing disappearing, it will mean billions of additional subordinated bond issuance and potentially some widening margin pressure for new issues if demand growth doesn’t match supply growth.

That could result in tighter margins for hybrids, and higher prices. So, there may still be an opportunity for 6-7% returns in this space.

The easiest way to get hybrids exposure is via Betashares Australian Major Bank Hybrids Index ETF (ASX:BHYB).

If you want an expert in this area, Elstree Investment Management is well regarded and has a listed ETF, The Elstree Hybrid Fund Active ETF (Cboe:EHF1).

Another ogood ption is the Schroder Australian High Yielding Credit Fund (Cboe: HIGH).

Dividend ETFs

If cash is the least risky investment, and bonds are second, then equities are riskier still, but they offer higher potential returns in the form or capital gain and income. An advantage for the income investor is that dividends offer tax advantages that cash and bonds don’t, through franking credits.

The largest ASX dividend ETF is Vanguard’s Australian Share High Yield ETF (ASX:VHY). It sports a current dividend yield of 5%, or a grossed up yield close to 6.5%.

It’s worth noting that VHY has struggled to grow its dividend over the past decade because of its heavy exposure to financial and commodity stocks (73% of the portfolio). Financials, especially banks, haven’t been able to lift dividends much given limited earnings growth, while mining company earnings and dividends have suffered given the recent falls in many commodity prices.

Listed investment companies

Listed investment companies or LICs may be an option for those seeking high and growing dividend income.

Australian Foundation Investment Company (ASX:AFI) is one of the oldest and most reputable LICs. It currently offers a yield of 3.7%, or 5.3% grossed up.

A good alternative is Plato Income Maximiser (ASX:PL8) which has a current yield of 5.2% fully franked and has achieved 9.8% total returns including franking credits since it was launched in 2017.

The recently listed Whitefield Income (ASX:WHI) is also worth a look, as is Wilson Asset Management’s WAM Income Maximiser Limited (ASX:WMX), which is raising money for the fund to invest in both equity and debt, with the aim of delivering gross income returns of 6% per annum.

Equities

With the recent dip in share prices, it potentially offers more opportunities to buy companies at cheaper prices and better yields.

For steady, high dividend yielding stocks, here are three ideas:

Charter Hall Retail REIT (ASX:CQR). With rates more likely to dip than climb, property asset values are starting to stabilize after a rocky 24 months. CQR has $4.5 billion in neighbourhood retail assets plus some petrol stations. A lot of the assets are suburban sites with a supermarket and 5-10 retailers around that supermarket. Property occupancy remains high at almost 99%, and the average tenancy expires in seven years. CQR offers a healthy 7.3% net yield and trades well below its net asset value.

NIB Holdings (ASX:NHF) With an ageing population and increasing need for medical care, the long-term prospects for health insurers are favourable. NIB is the fourth largest health insurer behind Medibank Private, BUPA and HCF. While pricing is set by government, growing demand for private healthcare should ensure increasing earnings and dividends for many years. NIB offers a forecast net dividend yield of 4%.

Origin Energy (ASX:ORG) Origin is Australia’s largest electricity and gas supplier. Low wholesale electricity and carbon credit prices are going to make it tough for them to grow earnings over the next few years, though the company has defensive qualities that should make its dividend safe. Origin offers investors a 5.1% yield with reasonable valuations.

If you’re after growing dividends, then here are two stocks to consider:

Woolworths (ASX:WOW). I think it might be time to buy this supermarket giant. It’s had a terrible time of it lately – being trounced by Coles, having a change in management, plus the Government breathing down its neck, effectively capping grocery pricing. It’s left Woolies at less than a 20x price-to-earnings ratio, with earnings depressed because of the recent events. With a 3.4% forecast yield, I expect a comeback for this blue-chip stock.

Washington H. Soul Pattinson (ASX:SOL). A personal favourite of mine. The company has raised dividends in each of the past 24 years, by 10% per annum. A great track record and though the boss, Rob Millner, isn’t getting younger, the future still appears bright for the conglomerate. Soul Patts has a forecast 2.9% dividend yield.

* Note that Vanguard, Charter Hall, Schroders, and Macquarie Asset Management are sponsors of Firstlinks.

James Gruber is Editor at Firstlinks.

One thing many advisors can’t help but notice is how bad many clients are at making decisions.

This can be for any number of reasons: Maybe the client doesn’t care enough about the fine details of their options, maybe they get overwhelmed by the information available to them, or maybe they just can’t separate the emotion from the decision.

Regardless of why, that’s where behavioral coaching comes in—that is, decision-making support to help clients avoid common behavioral pitfalls. In terms of alpha, this is one of the most valuable services an advisor offers their clients, adding somewhere between 100 and 200 basis points. Yet, research on the topic has found clients don’t necessarily see behavioral coaching as valuable when asked to rank it alongside other advisor attributes.

Or do they?

In our recent work on what investors value in working with an advisor, we examined the results of three different methodologies across four studies. In three of the four studies, we found that items associated with behavioral coaching actually surfaced as one of the most valuable things to investors—they may just not define it as “behavioral coaching.”

Why Clients Don’t Say They Value Behavioral Coaching

For one, clients might not know what behavioral coaching even is. After all, “behavioral coaching” is a technical term many likely haven’t encountered in their daily lives.

We saw evidence of this in our findings. Often, people were able to identify behavioral coaching as something they valued either by using their own words to describe what they liked or by seeing an example of what behavioral coaching looks like. For example, clients said they appreciated having an advisor who could do any number of things like keeping their behavior in check during market volatility, explaining complex financial topics to them, and serving as a sounding board during the decision-making process. All these services are behavioral coaching, but those aren’t the words clients use to capture these offerings.

Second, it can involve admitting wrongdoing. We want to look good to others and ourselves; admitting that we need help with our behavior is not something most people are keen on vocalizing—especially when it comes to something important like money. In our findings, we saw some evidence that people were more responsive to the idea of behavioral coaching when they felt like it was the product of a collaboration between them and their advisor, instead of just their advisor leading them by the hand.

This reveals an interesting paradox for advisors: Behavioral coaching is both objectively and subjectively valuable, but clients may feel chafed at the suggestion that their behavior is a problem.

Fortunately, our findings reveal ways forward for advisors who want to elevate the value they bring as behavioral coaches without alienating clients.

Client-Friendly Ways to Provide Behavioral Coaching

For Prospective Clients

Advisors should ensure they broach behavioral coaching in a conscientious manner. Whether or not clients call it by name, behavioral coaching is one of the most common reasons they hire an advisor, so it’s important to advertise this skill to clients.

Advisors can do so in a few ways. For one, they can use wordings that have been found to be less controversial to clients. This could mean explaining how you help clients navigate “common behavioral pitfalls” or serve as a “sounding board” for clients when they make decisions.

You can also illustrate this skill for clients. One way to do this is to find places in testimonials where your clients highlight how you have made it easier for them to make decisions. Another way to do this is through examples, such as illustrating how you helped a client realign with their goals when they were tempted to walk away from their plan and the results that followed.

For Existing Clients

You want to ensure you are showing the value of your behavioral coaching, as opposed to telling them (like you might do with prospective clients).

This requires evaluating your practices and interactions with clients and identifying places where you can better provide behavioral coaching. For example, how do you explain different investment options to clients? Do you give them stacks of literature on each or launch into a long-winded explanation? If so, you might consider developing a decision support tool. These can be as simple as creating a table and identifying key features your clients may care about and how their options stack up on these features.

Another place you may consider beefing up your behavioral coaching is in helping clients prepare for volatility. Many people feel compelled to fiddle with their finances when volatility hits, and they don’t always consult with their advisor before doing so.

Therefore, you may take the time to develop contingency plans for them based on negative events. If something bad happens, what should they do? By establishing the action ahead of time (say, calling their advisor), you can help them commit to good decisions when it’s easy to do so. That means when things go awry, they just have to follow through with the plan—no thinking needed.

Such plans can have a high impact for clients because it will provide them peace of mind when they need it the most.

Don’t Be Scared Away From Behavioral Coaching

When asked directly, clients may make it seem like “behavioral coaching” is not a priority. But when clients explain what they value in an advisor, it often comes to the top of the list. That’s why enhancing your behavioral coaching skills is key to helping you better serve your clients.

February 2025 reporting season is behind us. Of 175 companies we cover scheduled to report during the month, all but one (Star Entertainment (ASX:SGR)) have announced. How did reporting season shake out?

To assess whether a reporting season exceeded, undershot, or met our expectations, we look at how our analysts changed fair value estimates. Our fair value estimate is a long-term valuation for a business, based on our discounted cash flow model. To estimate fair value, our analysts forecast a business’s future cash flows, discount these back to today, and then add them together.

If we increase our fair value estimate, the sum of all cash flows we expect the business to generate in the future, discounted to today, is greater now than before. Conversely, if we cut our fair value estimate, it generally indicates a business disappointed and now looks like it will generate less cash in the future.

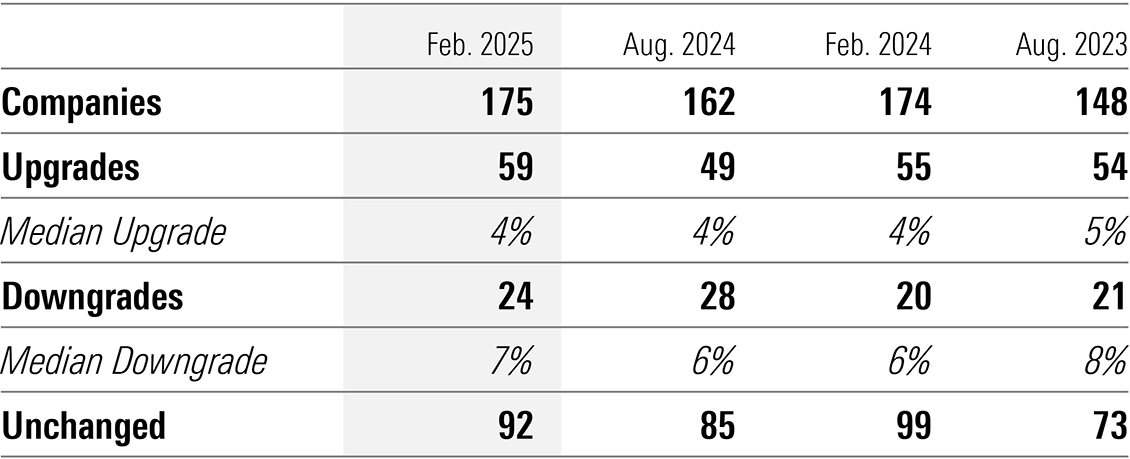

Table 1 shows fair value estimate changes during the month. For comparison, I’ve also included summary statistics for recent reporting seasons.

Table 1: Reporting season fair-value estimate changes

What stands out is how ‘normal’ February looks, despite all the media noise and some wild swings in the market. We upgraded about a third of companies we cover—very close to the historical proportion—and a median upgrade of 4% is bang in line with recent years. At roughly 15%, downgrades accounted for a typical share of total results, and a median of 7% is about average. Drilling down to individual stocks, we made some material changes at both ends of the spectrum (more on that later), but overall, things appear pretty typical.

Stock prices versus fair value

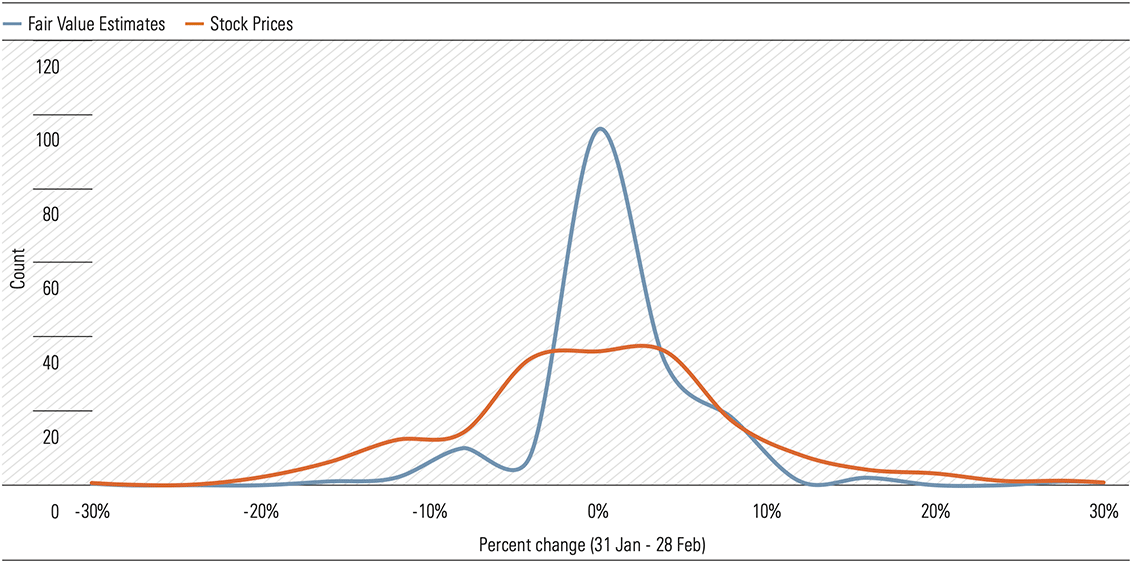

So to us, a fairly unremarkable set of results. But you wouldn’t get that impression from the market’s reaction. To see what I mean, let’s compare the distribution of stock prices and fair values during February [Exhibit 1]. Two things stand out.

Exhibit 1: Stock prices vs fair-value estimates

1. Market reacted far more negatively than we did

In terms of stock market performance, February 2025 was one of the worst reporting seasons in the last 20 years. A 3.4% correction for the ASX 200 during February is exceeded by only a handful of reporting seasons, including February 2009 (the global financial crisis) and February 2020 (the pandemic). We can’t attribute the entire selloff to results—Trump’s tariffs played a role— but they were a factor.

Per Exhibit 1, roughly 50% of stock prices for companies we cover wound up in the red during February. Meanwhile, we revised down only 15% of our fair value estimates during the month. How do we explain the difference?

It could be expectations. As discussed last week, we’ve argued that the market, and particularly large cap valuations, have looked stretched for some time. Opportunities abound amongst the smaller companies, but large caps, which dominate the market cap-weighted benchmark index, are richly priced. And perhaps this explains the severe reaction to the results: earnings failed to live up to the market’s lofty expectations.

2. Stock prices were more volatile than fair values

We also find that stock prices were far more dispersed than fair values. Put another way, the tails of the distribution are fatter. Of the 175 companies included in Exhibit 1, we didn’t change fair value for about half, hence the sharp peak at 0%. But of these companies, stock prices for only 36 stayed within ±2% of the value at the start of February.

Stock prices don’t always reflect the true value of a business. They also tend to swing around a lot more. Take Commonwealth Bank (ASX:CBA), for example. At the start of 2024, we estimated CBA’s fair value at $90 per share. Today, we estimate CBA shares are worth $98. So, the outlook has improved a little, though some of this is due to the time value of money (for a growing perpetuity, the present value increases over time even if forecasts don’t change).

Meanwhile, CBA’s stock price has catapulted from $110 to almost $160. To believe the market is correctly valuing CBA now, and at the start of 2024, you need to believe all the cash the bank will ever earn, discounted to today, is now 40% higher than a year ago. Maybe CBA has become a better business, but that much better? We might be wrong on our valuation, but even if we just consider the magnitude of the change, I find it easier to believe a blue chip, bellwether stock like CBA is 10%, not 40%, better than a year ago.

Undue bouts of volatility, like we saw in February, can present opportunities for patient, rational investors. A few of our Best Ideas, including Domino’s Pizza (ASX:DMP) and Endeavour (ASX:EDV), were met with sharp, and in our opinion, unwarranted selloffs. If the fundamental picture hasn’t changed— and for these businesses, we don’t think it has— investors can now pick them up for less.

The big upgrades and downgrades

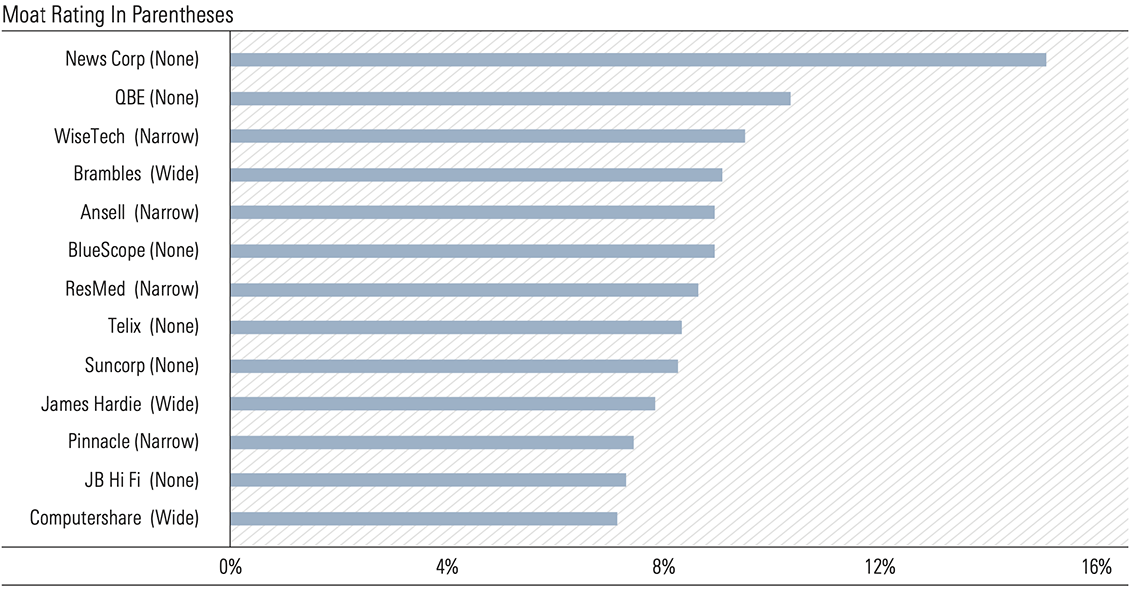

While reporting season was fairly typical in aggregate, we made some big valuation changes to specific stocks.

We saw a number of upgrades related to the weakening Australian dollar, which boosts the value of USD-denominated earnings. But we also saw improving fundamentals, particularly for moat-rated companies, which accounted for an outsized proportion of our biggest upgrades [Exhibit 2]. This included WiseTech (ASX:WTC), Brambles (ASX:BXB), Ansell (ASX:ANN), ResMed (ASX:RMD), James Hardie (ASX:JHX), Pinnacle (ASX:PNI), and Computershare (ASX:CPU). Perhaps this isn’t surprising: history shows us that the intrinsic compounders, which get better as they grow, are more likely to exceed expectations than the run-of-the-mill, cost-of-capital businesses.

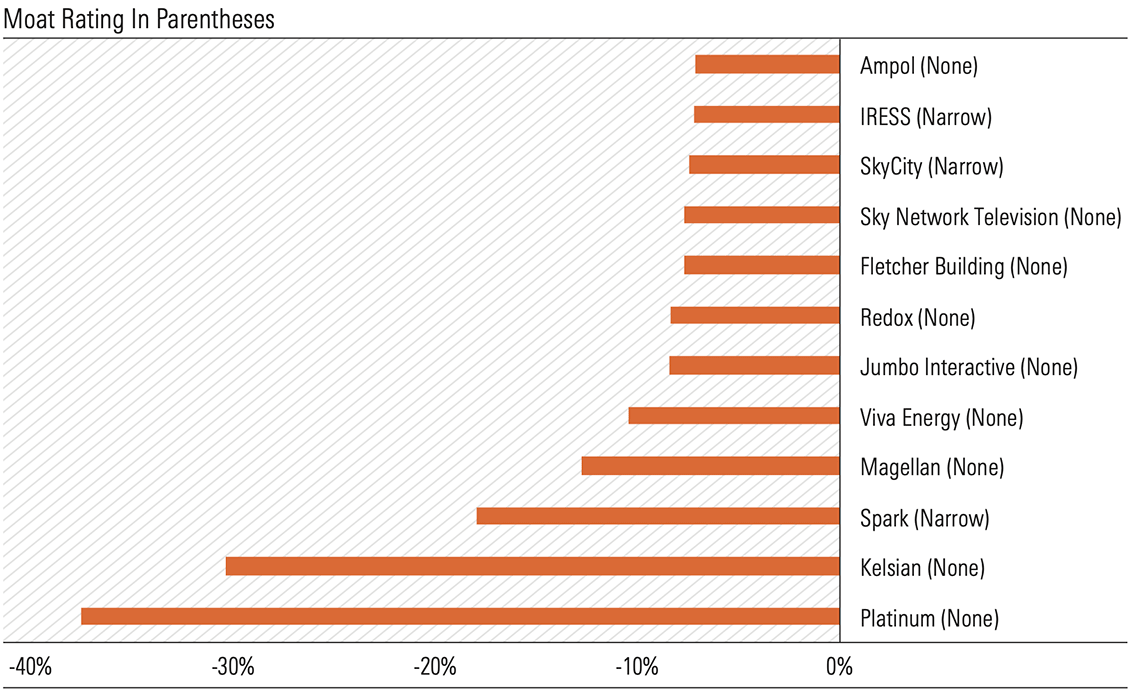

Exhibit 2: Reporting season fair-value estimate upgrades of 7% or more

Across the downgrades, a few themes emerge [Exhibit 3]. For starters, no-moat companies accounted for the lion’s share—a stark contrast to the types of businesses that earned our biggest upgrades. Embattled asset manager Platinum (ASX:PTM) suffered our biggest downgrade, 38%, in part due to the exit of two high-profile portfolio managers, and the implications for funds under management. For a similar reason, we downgraded Magellan (ASX:MFG) 13%. We believe it’s extremely difficult to carve out a moat in the asset management industry, and the fate of Platinum and Magellan, two former industry titans and market darlings, speaks to this theme.

Exhibit 3: Reporting season fair-value estimate downgrades of 7% or more

It becomes harder to identify a common theme across the rest of the downgrades, which were largely idiosyncratic. For example, the performance of Kelsian’s (ASX:KLS) recently-acquired US coach business disappointed, and a lower outlook for long-run margins wiped 30% off our fair value estimate. Meanwhile, Spark’s (ASX:SPK) third guidance downgrade over the past year suggests the company’s cost base is fundamentally more bloated than we thought and not agile enough to respond to unexpected revenue weakness. We cut our fair value estimate 17%, the third biggest downgrade in February.

For more reporting season insights, including our key takeaways across banks, telcos, miners, REITs, and supermarkets, see our previous editions of Your Money Weekly, issue 6 (published 21 Feb. 2025) and issue 7 (published 28 Feb. 2025).

Key takeaways

- Separate signal from noise and focus on fundamentals and valuations.

- Even after outperforming, we continue to recommend value stocks over growth.

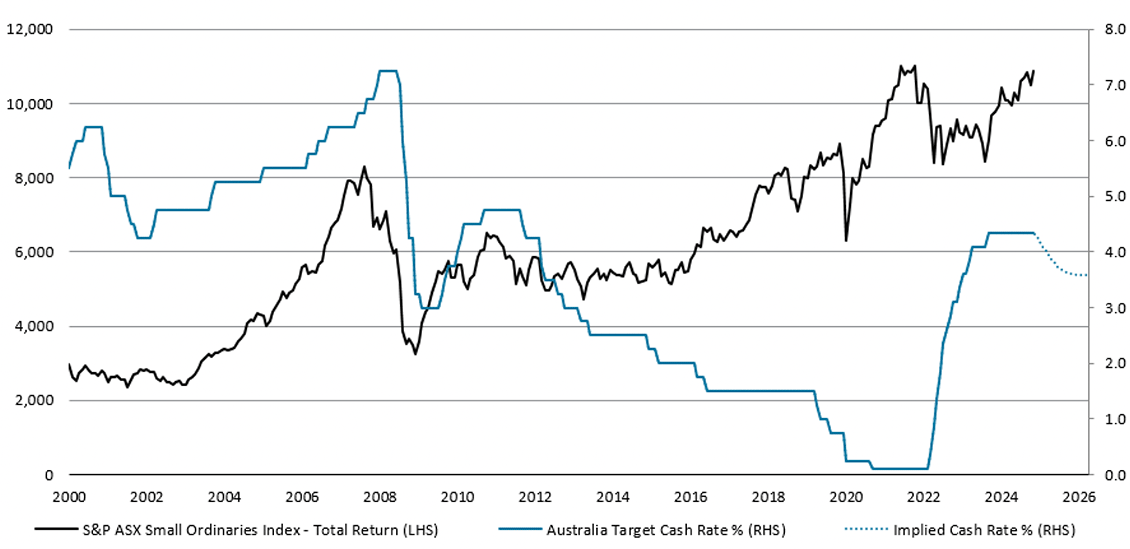

- Small-cap stocks have failed to deliver but remain attractive.

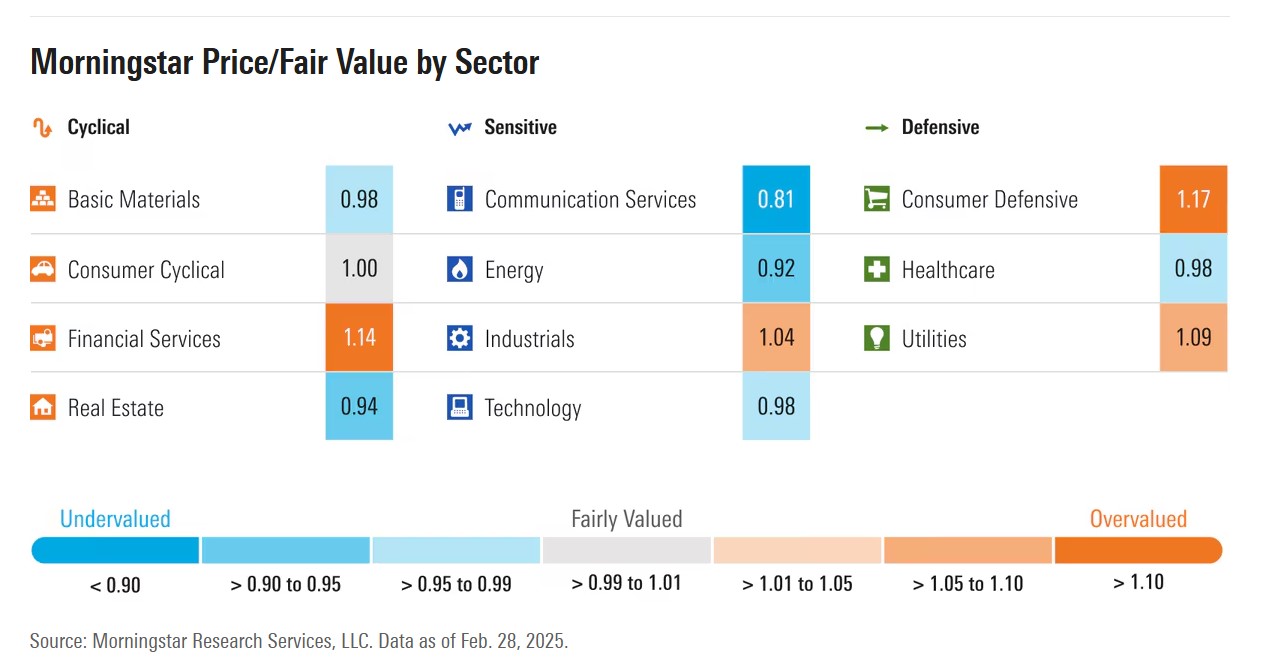

- Sector valuations are generally consolidating toward fair value.

Focus on the fundamentals, ignore the noise

One of the hardest aspects of investing is separating signal from noise. Divining between news that identifies a paradigm shift that will either positively or negatively affect earnings (signal) versus news that garners a lot of attention yet will not meaningfully impact a company’s business (noise).

Only two months into the year and it already feels like we have had a full year’s worth of headlines. From earnings and guidance, to the DeepSeek scare, to President Donald Trump’s on-again, off-again tariffs, volatility has risen anew.

In such an environment, what’s an investor to do? Investors should focus on the fundamentals, maintain a long-term mindset, and pay attention to valuations. And that is just what our analyst team is doing, scrutinizing the long-term fundamentals underlying sector outlooks and analyzing the long-term assumptions that drive our valuation models.

Considering how fluid the situation remains as to the threats of implementing tariffs, once we have specificity on the amount of tariffs that will be implemented and a base case as to how long those tariffs may last, we will adjust our projections and valuations accordingly.

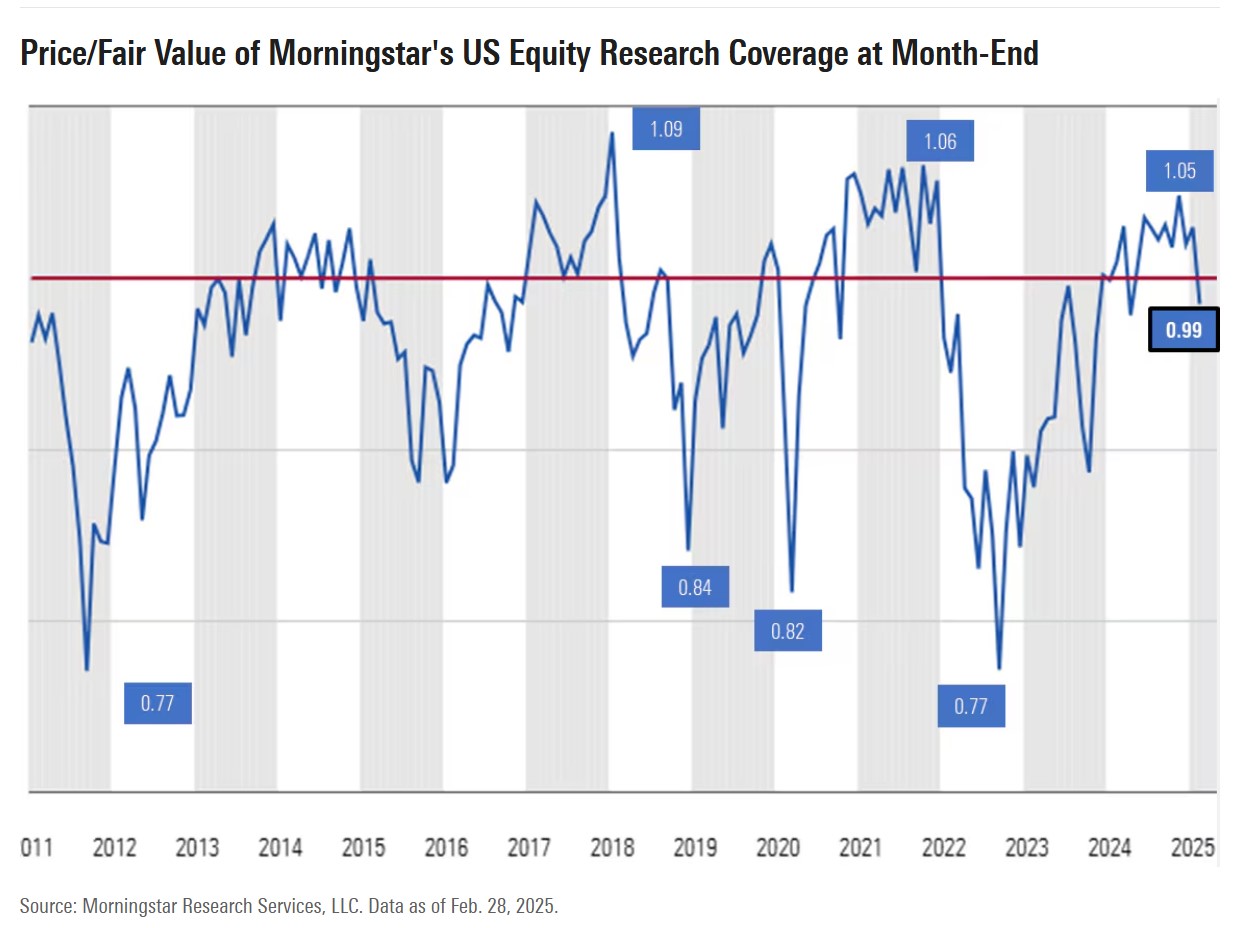

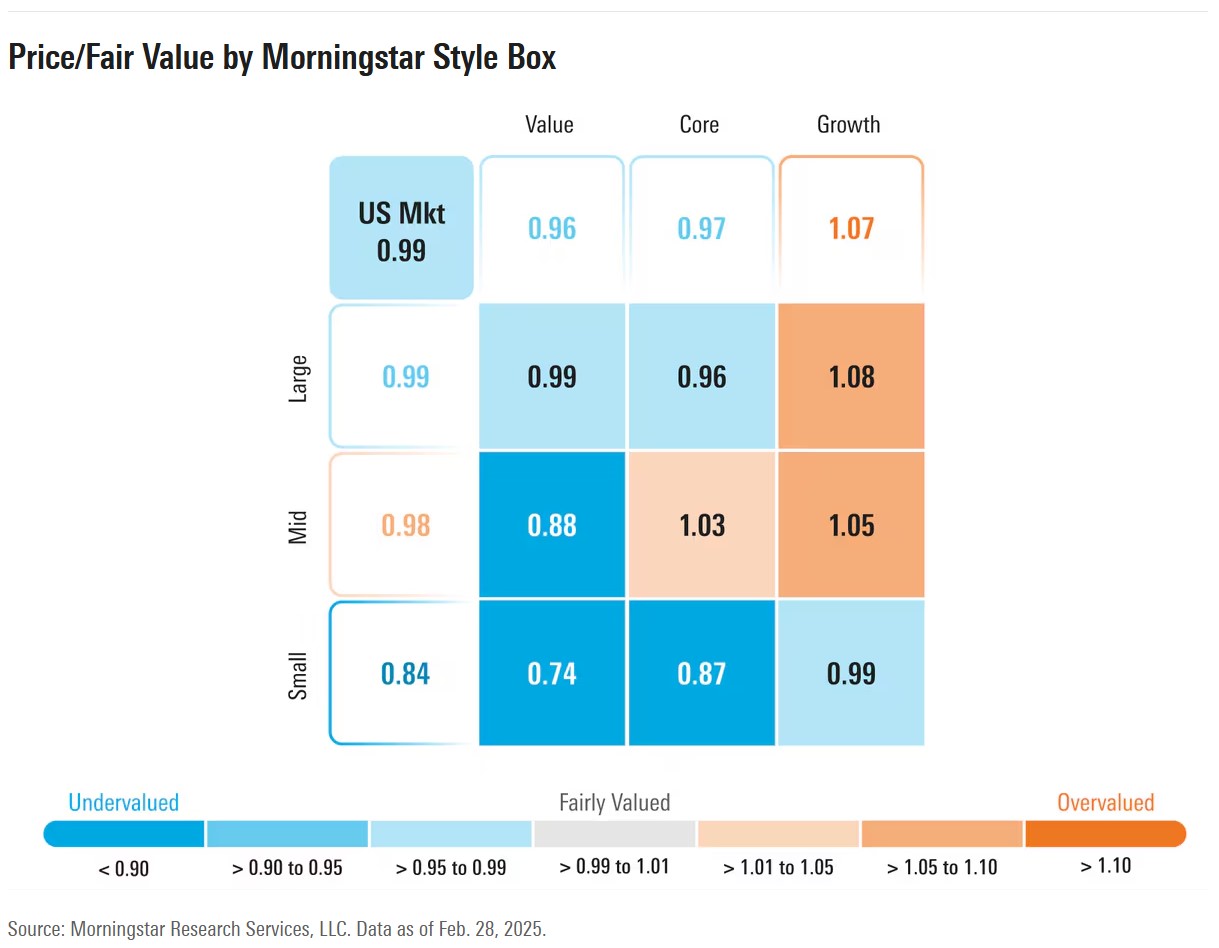

US stock market valuation and outlook

As of Feb. 28, 2025, according to a composite of our valuations, the US stock market was trading at about a 1% discount to fair value. That was the first time since a year ago (when stocks pulled back following inflation data that led to a shift in interest-rate expectations) the market has traded at a discount to a composite of our fair values.

Value is significantly outperforming growth

In the 2025 US Market Outlook, we highlighted that the US stock market was bumping up against the upper end of our fair value range and investors should temper their return expectations for this year. In fact, since the end of 2010, the market had traded at that much of a premium or higher less than 10% of the time. With the market trading at the high end of our fairly valued range, we noted that we had become progressively cautious and positioning is increasingly important.

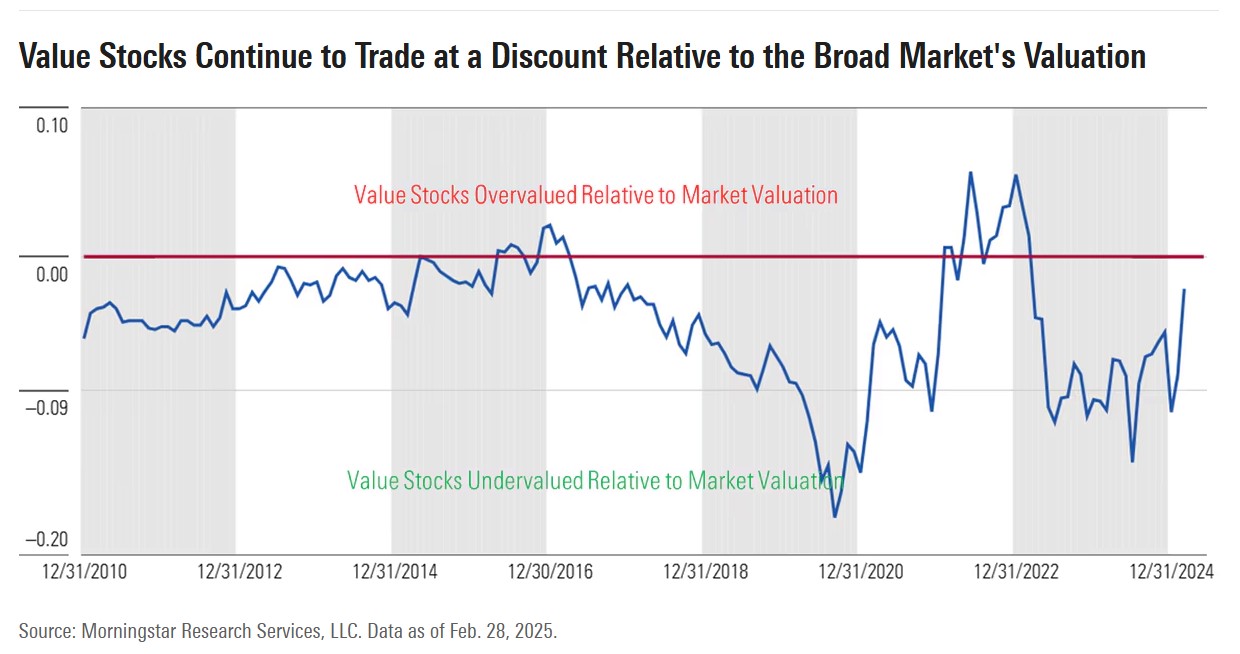

As such, we recommended that investors overweight value stocks and underweight growth stocks, as growth stocks were trading at the highest premium over fair value since the disruptive tech bubble in early 2021, yet value stocks were still undervalued. For the year to date through March 3, 2025, the Morningstar US Value Index was up 5.54%, whereas the Morningstar US Growth Index was down 3.81%.

According to our valuations, on both an absolute and relative value basis, we think the rotation into value stocks still has room to run. Not only are value stocks more attractively valued, we think the rotation into value will pick up steam as the economy slows and growth stocks’ earnings growth begins to slow.

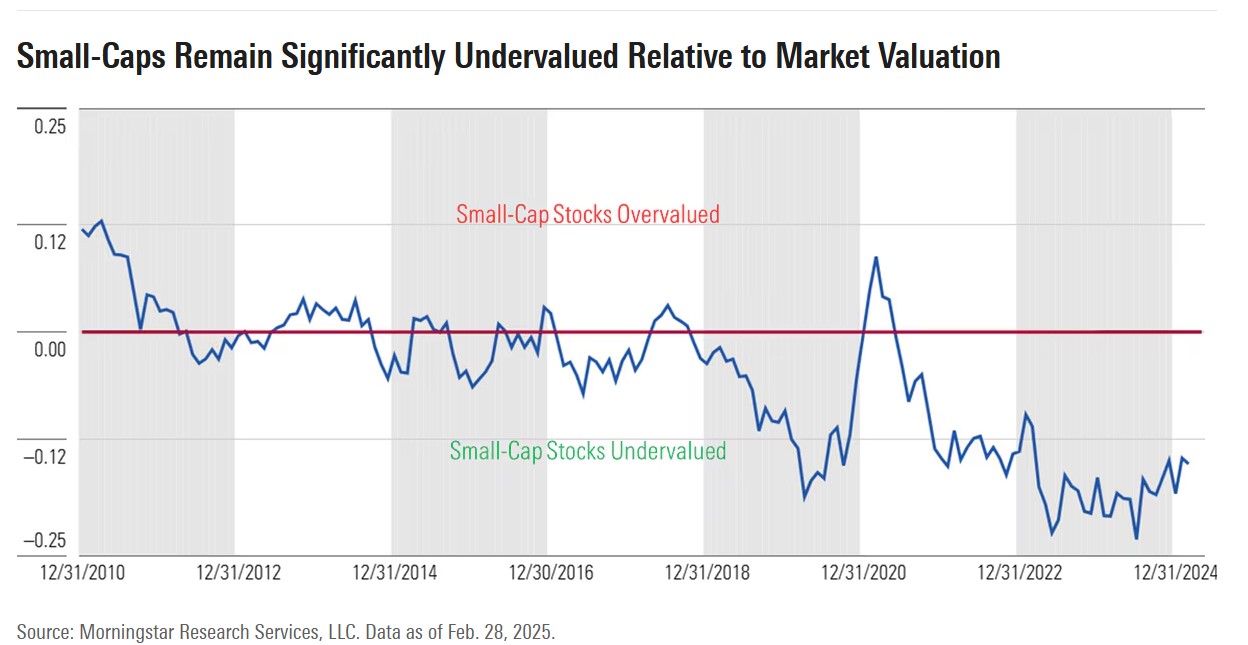

We also continue to see an opportunity in small-cap stocks, which remain undervalued compared with the broad market on both an absolute and relative value basis.

Are the Trump tariffs coming to fruition?

In our 2025 outlook, we had also stated that “the bigger wild card in the first quarter will be what President Donald Trump may or may not do regarding his assertions to implement new tariffs.” That assertion is coming to fruition. Yet, for now, this may mostly be noise as it will be the final resolution of the tariff negotiations that will affect long-term valuations.

The questions now are: What will be the final resolution of the tariff negotiations with both Canada and Mexico as well as China? Which products will be tariffed, and which may be excluded? How much will the tariffs be? How long will tariffs last? What retaliatory tariffs will be instituted in response? These details will have significant implications on corporate margins and stock valuations.

Looking forward, we expect there will be a wide range of valuation outcomes from a little to a lot, depending on the amount of margin compression and how long that compression will last.

We expect that Canadian oil producers would be significantly negatively affected as a 10% tariff makes overseas medium and heavy crude more attractive to US midcontinent and Gulf refiners. Examples of other Canadian products that could be hit include lumber and potash.

Companies with facilities in Mexico, such as automakers Ford F and General Motors GM and power sports equipment maker Polaris PII, would be unlikely to quickly pass through tariffs. In addition, distributors of Mexican products, such as Constellation Brands STZ, would have difficulty quickly passing through price increases.

Examples of sectors that would be negatively affected by higher tariffs on Chinese imports include apparel and apparel retailers, such as Macy’s M and Kohl’s KSS, which lack the pricing power to push through cost increases. Best Buy BBY could be under especially intense pressure as China accounts for 60% of its cost of goods sold, and Mexico is the company’s second-largest source. Similarly, technology companies like Apple AAPL that import electronic goods from China would have to raise prices substantially to maintain their margins.

Yet not all companies would be negatively affected. Companies that have greater domestic sourcing or source from areas not subject to tariffs as compared with their competitors may benefit. Other companies that have strong pricing power may be able to quickly pass through those added costs, and assuming only a modest pullback in volume, could see their earnings rise.

Positioning remains especially important

In such a volatile market in which economic policy can lead to such a quick change in valuations, portfolio positioning remains especially important. No matter how the tariffs may play out in the short term, we think investors should look to overweight those areas trading at a significant margins of safety below their long-term intrinsic values and underweight those areas that are overvalued.

Based on our valuations by market capitalization, we recommend that investors:

- Overweight small-cap stocks, which trade at a 16% discount to fair value.

- Market-weight mid-cap stocks, which trade at a 2% discount to fair value.

- Slightly underweight large-cap stocks even though they trade at a 1% discount because they are more highly valued than small-caps on a relative basis.

By style, we recommend that investors:

- Overweight value stocks, which trade at a 4% discount.

- Overweight core stocks, which trade at a 3% discount to fair value.

- Underweight growth stocks, which trade at a 7% premium to fair value. While the premium has dropped considerably as growth stocks have sold off, it remains at a high premium to our valuations.

Sector valuations are consolidating

With growth stocks selling off and value stocks appreciating, we have seen our sector valuations consolidate toward fair value as overvalued sectors have become less overvalued, and undervalued sectors have become less so. For example, healthcare, real estate, and basic materials were some of the more undervalued sectors at the beginning of the year, but each has moved closer toward fair value. Among the overvalued sectors at the beginning of the year, consumer cyclical was the most overvalued and has since dropped to fair value.

Bucking the trend are communication services and consumer defensive. The communication-services sector has become more undervalued following several notable increases in our fair values on stocks such as Alphabet GOOGL and Meta META. Consumer defensive has become further overvalued and is now the most overvalued at a 17% premium. The three stocks that account for the greatest percentage of the sector’s market capitalization, Walmart WMT, Costco COST, and Procter & Gamble PG, have risen 7%, 12%, and 9%, respectively, for the year to date.

Get Morningstar insights in your inbox

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://video.morningstar.com/aus/sd/2025/250221_Interest_Rates_mstar.mp4?_=3Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://video.morningstar.com/aus/hd/2025/250211_ARC_Webinar_hd.mp4?_=4In his 2022 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter, Warren Buffett discussed the ‘secret sauce’ to investing, highlighting growing dividends at two of his long-term holdings: Coca-Cola (NYSE:KO) and American Express (NYSE:AXP).

Berkshire bought shares of Coke for a total cost of US$1.3 billion in 1994. The cash dividend that Berkshire received from Coke in that year was $75 million. By 2022, the Coke dividend paid to Berkshire was US$704 million.

Of this, Buffett said: “Growth occurred every year, just as certain as birthdays. All [business partner Charlie Munger] and I were required to do was cash Coke’s quarterly dividend checks. We expect that those checks are highly likely to grow.”

American Express has been a similar story. Berkshire completed the purchase of the company’s shares in 1995, also for US$1.3 billion. Annual dividends from Amex grew from US$41 million then to US$302 million in 2022.

The dividend growth from these companies has been incredible for both Berkshire and Buffett. The dividend from Coke grew 9.4x over the 28 years to 2022, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.3% per annum (p.a.).

The 2022 dividend from Coke represented an annual yield of 54% on Buffett’s original purchase price (it’s now 60%). In other words, for every dollar that Buffett invested in the company, he’s now getting 60 cents in annual dividends. In total, he’s received US$10.72 billion in dividend income, against a cost of US1.3 billion, and he’s used that dividend money to buy stakes in other businesses and shares through the years.

Likewise, American Express grew dividends by 7.4x over 27 years, at a CAGR of 7.7%. Buffett is now getting an annual dividend yield of 23% on his original purchase price.

The wrong conclusion to draw from this is that Buffett bought these companies for their dividends. He didn’t. Amazingly, Coke did offer close to a 6% yield in 1994 because Buffett bought it on the cheap. By contrast, his purchase of America Express was when the stock was on a yield of about 3.2%.

But Buffett purchased Coke and American Express because of their ability to grow earnings over the long term. The dividends were merely a by-product of the earnings growth. Without the earnings power of the companies, dividends wouldn’t have been able to increase at the clip they did.

Earnings drive dividends

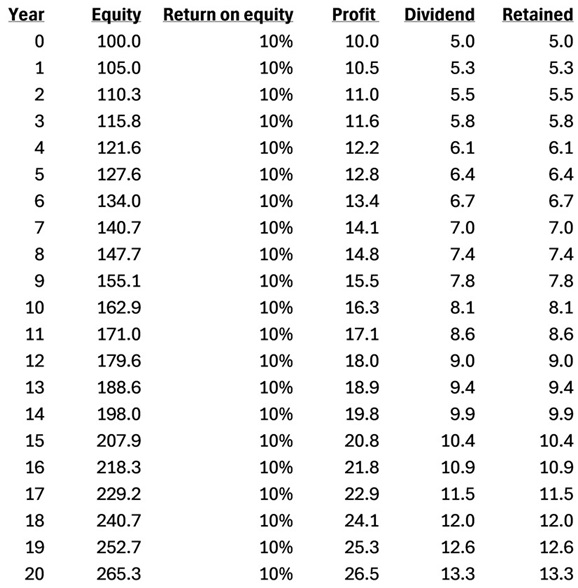

An example can illustrate the point. Let’s take a stock called ‘Good Dividend Yield Corp’. The business has $100 dollars in equity, and it makes a reasonable return on that equity of 10%, resulting in $10 worth of profit. Of that profit, it pays out 50% as a dividend, equivalent to $5. It retains the remaining $5 in earnings for reinvestment in the business.

Figure 1: Growth of profits and dividends in ‘Good Dividend Corp’. Source: Author

I buy this stock for $100. That equates to a price-to-earnings (PE) ratio of 10x and a dividend yield of 5%.

By year 20, the company has increased profits to $26.50 from $10. Dividends are up from $5 to $13.30, at a CAGR of 5%. By year 20, the annual dividend yield at cost for the business is 13.3%.

If the shares trade at a similar PE ratio of 10x, they would be worth $265.50 in year 20. That would equate to a share price return of 5% p.a. ex-dividends. Not too bad.

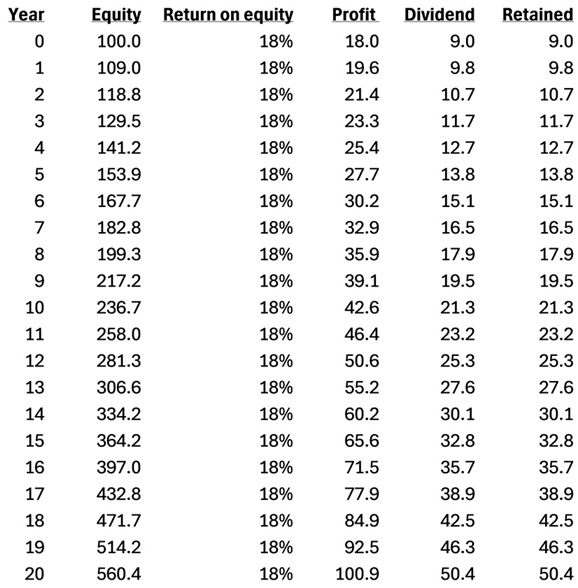

Let’s now look at another company called ‘Faster Growing Corp’. This business has $100 in shareholders equity but earns a better return on equity of 18%, resulting in net profit of $18. Of that profit, it pays out 50% as dividends, equating to $9. It retains the remaining $9 in earnings for reinvestment in the business.

Figure 2: Growth of profits and dividends in ‘Faster Growing Corp’. Source: Author

I buy this stock for $350. That puts it on a PE ratio of 19.4x – not cheap but probably fair given the growth in the company. The dividend yield is 2.6%, lower than I’d like.

By the end of year 20, ‘Faster Growing Corp’ has increased profits to $101 from $18, up 5.6x, at a CAGR of 9%. Dividends have followed suit, growing from $9 to $50.40 over the same period, also a 9% CAGR.

By year 20, the annual dividend yield at cost for the business is 14.4%. In other words, though ‘Faster Growing Corp’ had a dividend yield about half that of ‘Good Dividend Yield Corp’ in year 0, the yield at cost for the former had risen to more than latter by year 20.

That’s not the full story, though. If we assume the same PE ratio for ‘Company B’ of 19.4x at year 20, the stock price would be $1,941, up from $350 at initial purchase, equivalent to a return of 9% p.a. ex-dividends.

By the end of year 20, ‘Company B’ has a higher dividend yield at cost, a faster growing dividend, all the while having achieved a higher total return over the preceding period.

The lesson is that earnings drive dividends. You want to own businesses that can grow earnings over the long term and pay out a portion of those growing earnings as dividends over time. By doing this, you stand a chance of being in the enviable position that Buffett is with Coke and American Express.

Another way to maximise dividend income

The other overlooked aspect of dividend investing is the importance of reinvesting dividends.