The Government has struck a compromise in its desire to rein in the cost of tax concessions on large superannuation balances. Treasurer Jim Chalmers has announced that taxation on earnings from superannuation balances in excess of $3 million will double to 30%. The existing 15% rate on accumulation funds will continue for all super balances below $3 million. Chalmers said:

“The modest adjustment we announce today means 99.5% of Australians with superannuation accounts will continue to receive the same generous tax breaks, and the 0.5% of people with balances above $3 million will receive less generous tax breaks.”

However, there is a surprise in the way the extra tax will be calculated, as outlined below. Not only will the Australian Taxation Office issue tax liability notices to individuals for the first time in the 2026-27 financial year, but earnings will include unrealised capital gains.

Although holders of large super balances will be hit by the higher tax, the fears of a hard cap forcing the removal of money from super, or the imposition of tax at the top personal marginal rate, have not been realised. The delay until after the next election also gives time for consultation and modification.

Managing the politics

Although the Government had previously indicated it was only having a ‘conversation’ with the Australian people, it has moved quickly with an announcement in the face of growing criticism. Crucially, the attack on the Government was labelled a breach of an election promise and it raised the prospect of undermining the ‘truth and integrity’ high ground Prime Minister Anthony Albanese campaigned on successfully at the last election. Albanese was especially vulnerable after his undertaking in the May 2022 election campaign:

“We’ve said we have no intention of making any super changes. One of the things we’re doing in the election campaign is we’re making all of our policies clear.”

By postponing the effective date until after the next Federal election, due by May 2025, Labor can claim it took the policy to the people, thereby not breaking an election commitment. Chalmers will argue he has addressed some of the growing cost of superannuation concessions. On the other hand, those affected have three more tax returns at the lower rate assuming Labor wins again.

Both sides blinked at the same time and a middle ground was reached.

It’s worth noting there are many assumptions in the $48 billion estimated cost of superannuation concessions, such as the guess that earnings outside super would be taxed at the top marginal rate, whereas it is more likely that many people would find alternative ways to reduce their tax.

The new policy is expected to raise about $2 billion a year. Earlier in the debate, Chalmers suggested he preferred a cap of $3 million on the amount that can be held within super, with the rest removed. He probably wanted to avoid the spectre of increasing taxes, but it would have been an inferior approach. Imposing a $3 million cap would have required the removal of money from superannuation, creating a range of complexities such as forced sales of illiquid assets and realising capital gains in a tax event.

How will the new tax work?

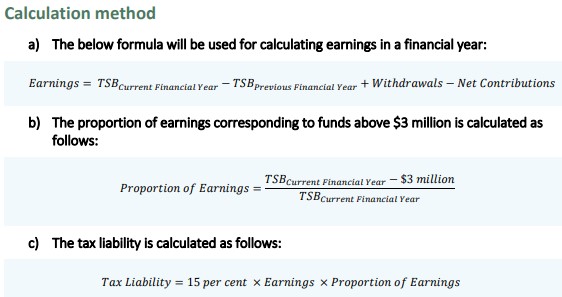

Treasury has issued a Fact Sheet on how the tax will be calculated, based on the increase in individual balances rather than imposing a tax on a super fund. There remains no limit on the size of account balances in the accumulation phase.

Each person will have a Total Superannuation Balance (TSB) and those with over $3 million at the end of a financial year will be subject to a tax of 15% on earnings. Earnings will be calculated using the difference between the TSB at the start and end of consecutive financial years, adjusted for withdrawals and contributions.

Using the same treatment as adopted for Division 293 Tax (the extra tax paid on super contributions where income exceeds $250,000), individuals can choose whether to pay the tax from their super or from other resources. The new tax does not form part of a personal income tax return, and the limit is per person, not per fund such as an SMSF.

Treasury summarises the calculation as:

Tax Liability = 15% x Earnings x Proportion of Earnings over $3 million

The tax liability is calculated at 15% because earnings in accumulation are already taxed at 15%, and this is an additional tax.

It’s easier to understand with their worked examples. The surprise is that earnings include unrealised gains and losses. TSBs will be tested for the first time on 30 June 2026 with tax liability notices issued in 2026-27.

Treasury’s example on a balance exceeding $3 million

– Warren is 52 with $4 million in superannuation at 30 June 2025. He makes no contributions or withdrawals. By 30 June 2026 his balance has grown to $4.5 million.

– Warren’s calculated earnings are $4.5 million – $4 million = $500,000.

– His proportion of earnings corresponding to funds above $3 million is ($4.5 million – $3 million) ÷ $4.5 million = 33%

– His tax liability for 2025-26 is 15% × $500,000 × 33% = $24,750

Note that this is the extra tax, the additional amount above the tax that Warren would currently pay. That’s where the estimated $2 billion in revenue comes from.

Treasury’s example on the earnings calculation

– Carlos is 69 and retired. His SMSF has a superannuation balance of $9 million on 30 June 2025, which grows to $10 million on 30 June 2026. He draws down $150,000 during the year and makes no additional contributions to the fund.

– Carlos’s calculated earnings are: $10 million – $9 million + $150,000 = $1.15 million

– His proportion of earnings corresponding to funds above $3 million is ($10 million – $3 million) ÷ $10 million = 70%

– Therefore, his tax liability for 2025-26 is 15% × $1.15 million × 70% = $120,750

Again, this is an additional tax, not the full tax. Anyone with multiple super funds, such as an SMSF, retail fund or industry fund, can elect where the extra tax is paid from.

Treasury example of a carry-forward loss

– Dave is 70 and has two APRA-regulated funds and one SMSF. At 30 June 2025, his TSB across all funds was $7 million. During 2025-26, he withdraws $400,000 from his SMSF and makes no contributions. At 30 June 2026, his TSB across all funds is $6 million.

– This means Dave’s calculated earnings are $6 million – $7 million + $400,000 = minus $600,000.

– His proportion of earnings corresponding to funds above $3 million is ($6 million – $3 million) ÷ $6 million = 50%.

– The earnings loss attributable to the excess balance is $300,000. Dave can carry forward the $300,000 to offset future excess balance earnings.

– At 30 June 2027, Dave’s funds make earnings on his excess superannuation balance of $650,000. He carries forward the earnings losses attributable to his excess balance at 30 June 2026 of $300,000 and is only liable to pay the tax on $350,000 of earnings.

– This means his tax liability for 2026-27 is 15% × $350,000 = $52,500. (Treasury’s example incorrectly says $52,000)

Although it is another level of complexity, this method was chosen because funds do not currently calculate taxable earnings at an individual member level, and a method was needed to identify taxable earnings for members with balances over $3 million.

The major sting here is the inclusion of unrealised capital gains. For example, many investors in startup companies hold the asset in their SMSF, and such companies often face dramatic swings in valuations based on the last funding round. A member may enjoy a large valuation upswing on which tax is payable without receiving any actual cash, only to see the value fall the following year. The same applies for an SMSF holding a large equity allocation which rises one year and gives back the next.

There was no statement about whether people with over $3 million in super can stop new Superannuation Guarantee contributions from their employer and take a higher salary instead. Someone earning less than $45,000 incurs a marginal tax rate of only 19% and might prefer to invest outside super and avoid the 30% tax rate. The lack of indexing in the $3 million is inappropriate and will be a major point of contention.

The Treasury fact sheet is here.

Alternatives, politics and unrealised gains tax

Now watch for articles on alternatives to holding large amounts in super. The case for investing more in a family home, transferring super to a lower-balance spouse or family trusts just received a boost, as did the financial advice industry.

The politics has a long way to play out before the new tax rate hits the bank accounts of large super holders, and it’s likely the Coalition at the 2025 election will argue ‘typical Labor’ with tax increases to ‘pay for their spending’. Chalmers and Albanese will need to persuade voters that it is the right policy to reduce the cost of super. The Prime Minister gave a hint of what is to come when he said:

“If they (the Coalition partners) want to vote against this change and try and prevent this change, then they can explain to people why they’re not prepared to back energy bill relief for pensioners … but they are prepared to go to war for the one half of 1% of people with more than $3 million of superannuation in their accounts.”

The taxation of unrealised capital gains is the shock and the part of the policy likely to drive the most resistance and opposition. It will push some money out of super as many investors currently use their SMSF to hold growth assets with realised capital gains bumped far into the future.

The objective of super is next

Labor has yet to make a firm undertaking that there will be no further changes to superannuation. Yesterday, Jim Chalmers even refused to rule out capital gains on the family home, before Albanese quickly jumped in and corrected him.

For example, what might happen to lump sum withdrawals? The Government intends to legislate an objective of superannuation as follows:

Lump sum withdrawals seem incompatible with the objective. Under current arrangements, someone can withdraw all their superannuation on attaining one of the many ‘Conditions of Release’, such as reaching the age of 65, even if they have not retired. Taking all the money out seems to breach the objective “ … to preserve savings to deliver income” in retirement. So the question is … what’s next?

Graham Hand is Editor-at-Large for Firstlinks. This article is general information.

Morningstar

Morningstar