New forecasts from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) highlight how quickly our population will age, and investors need to prepare now for the enormous changes that it will bring.

For a start, it will put huge pressure on Government budgets as spending on health and welfare skyrockets. To pay for this, Governments will need to increase taxes, borrow and print more money, or cut spending on other things. A combination of all three options is possible. Further changes to superannuation and the Age Pension seems inevitable in this context.

The ageing population will lead to slowing growth in our working age population, or even an eventual decline. Fewer workers may mean a tighter labor market. Could that result in structurally higher inflation?

It will also affect valuations of stocks and sectors on the ASX. There should be long-term tailwinds for companies catering for our ageing population including private health insurance, retirement villages, hearing aids, annuities, and pharmaceuticals/biotechnology. Conversely, there will be headwinds for companies exposed to the young, including childcare, toys, and teenage fashion.

New life expectancy estimates

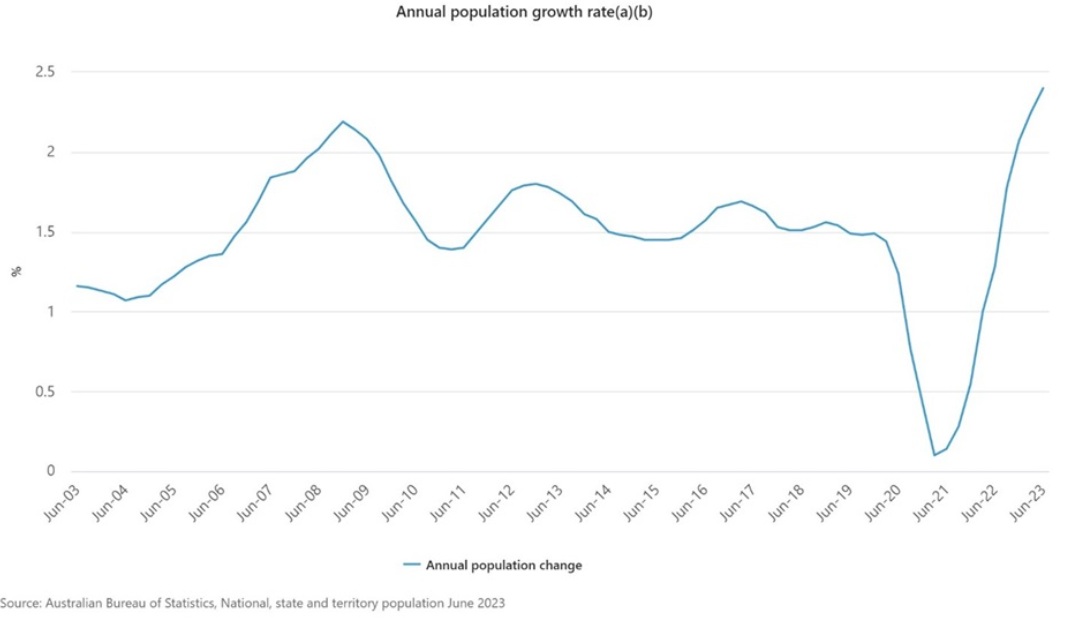

Recent population statistics from the ABS made front-page news. The data showed that Australia’s population had increased to 26.6 million, rising 2.4% over the past year.

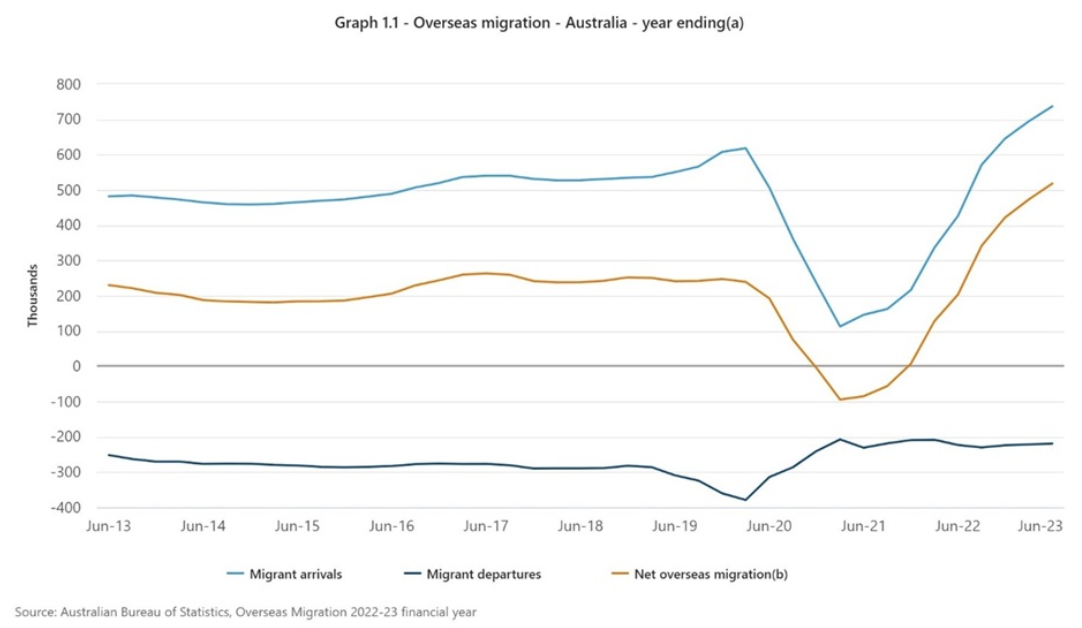

The headlines focused on the key driver for the increase in population: record high migration. In the year to June 2023, there were 737,200 migration arrivals and 219,100 departures, resulting in net overseas migration of 518,100. That figure was dramatically up from pre-Covid levels though it’s at least partially a catchup from Covid when numbers dipped sharply.

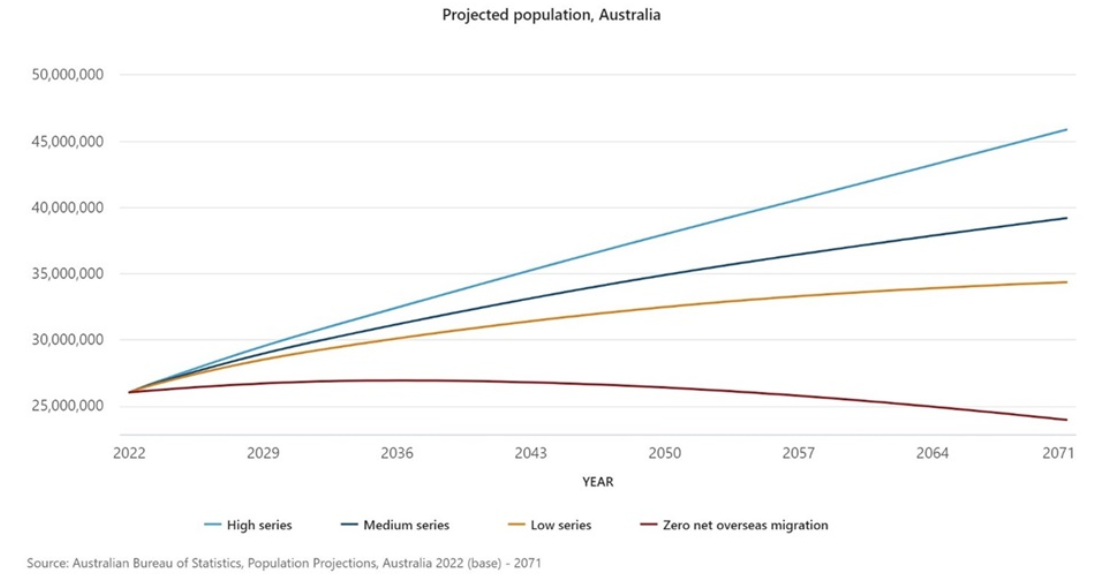

What didn’t grab headlines was data from the ABS on population projections and life expectancy. The ABS now forecasts that Australia’s population will rise from the current 26.6 million to between 34.3 and 45.9 million by 2071. That’s a large range and is based on the current 10-year average annual population growth rate of 1.4% falling to 0.2-0.9%.

The ABS forecasts the median age of 38.5 years will increase to 43.8-47.6 years. Taking the mid-range of that projection of 45.7 years means that the ABS is expecting a 20% increase in median age by 2071.

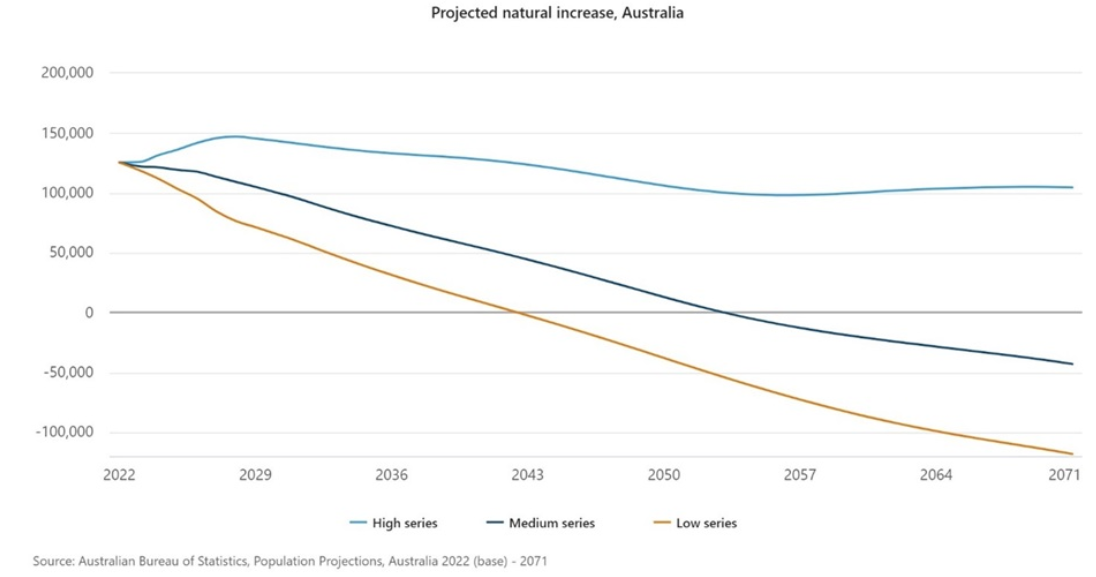

The ABS predicts that the natural increase in population could turn negative by as early as 2043. That means more Australians will be dying versus being born by then. That’s in the ABS’ so-called ‘low series’ scenario. Under its ‘medium series’ scenario, it’ll be 2054 when that happens, and under the high series, it won’t happen at all over the next 47 years.

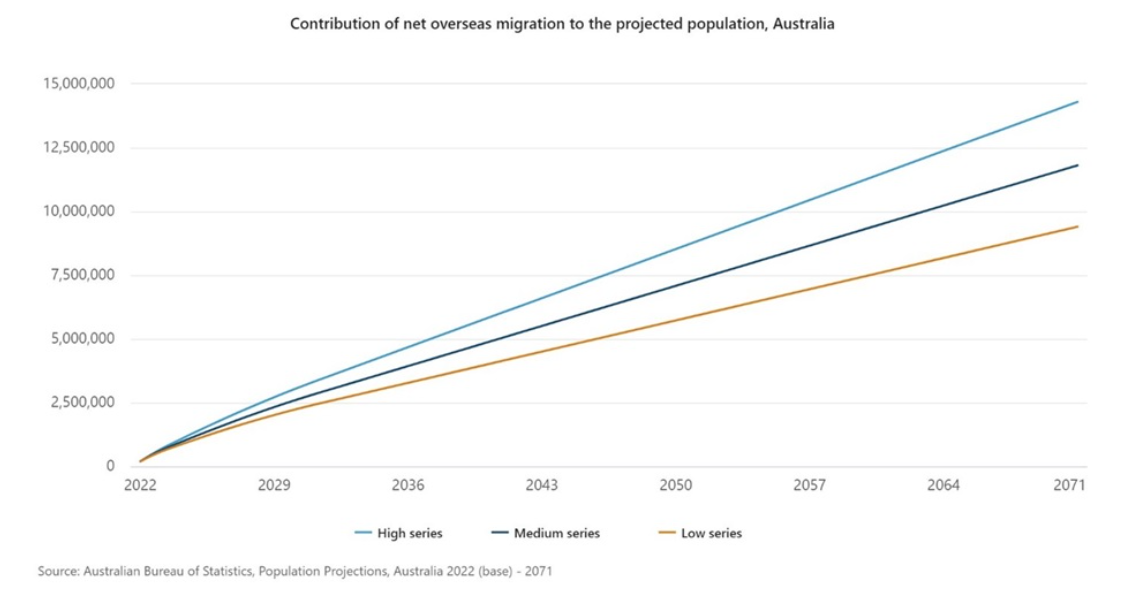

A big variable in the forecast is migration. The ABS forecasts that overseas migration will contribute 9.2-15.3 million people between now and 2071. The ‘medium series’ forecast of 11.8 million averages an annual intake of 246,000 overseas migrants.

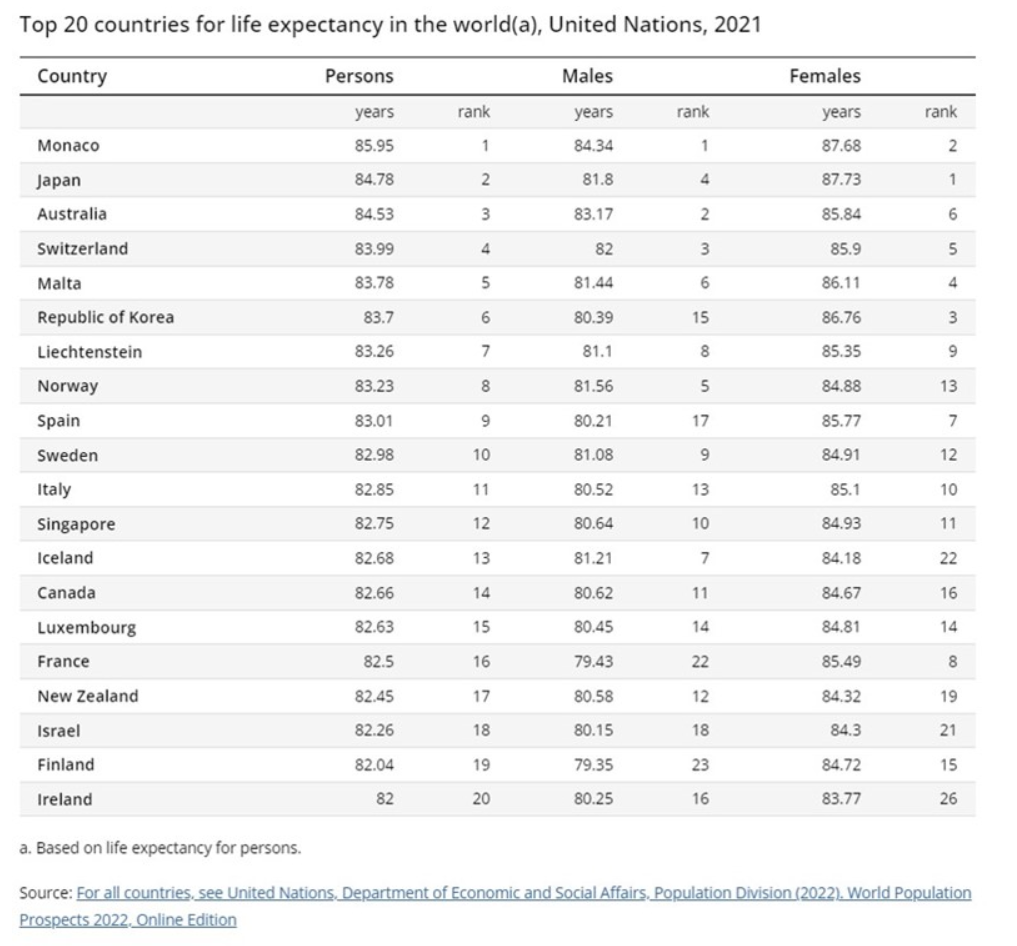

In other data, the ABS revealed that life expectancy at birth was 81.2 for men and 85.3 for women from 2020-2022. 30 years ago, those figures were 74.5 for men and 80.4 for women. In other words, men are living 6.7 years longer and women are living 4.9 years longer than they were in 1992.

Australia’s life expectancy now ranks third in the world behind Monaco and Japan.

The predictions for our ageing population aren’t new as the ABS, along with the various Intergenerational Reports, have continually updated their forecasts. As a rule, they’ve consistently underestimated life expectancy increases. This is understandable given that medical advances that extend life are impossible to predict. Yet it is also a fair bet that current estimates will prove too low as well.

A faster-than expected ageing of Australia’s population may mean we’re dealing with its effects far sooner than most think.

The great demographic reversal

A fascinating book called The Great Demographic Reversal outlines the potential impact from a rapidly ageing population on our economy. Written by Charles Goodhart, a Professor at the London Stock Exchange and former Chief Advisor to the Bank of England, and Manoj Pradhan, a macroeconomics consultant, in 2020, the book became well-known in economic circles for suggesting that higher global inflation was imminent. Back then, no one was suggesting that. The prediction turned out to be correct, albeit perhaps not entirely for the reasons that they put forward.

In the book, Goodhart and Pradhan argue that economic growth in the developed world is bound to fall because the tailwinds of the past three decades are now reversing.

Economic growth is a function of growth in working age population plus productivity growth. Goodhart and Pradhan suggest the days of a growing working age population are behind us and productivity improvements won’t be enough to offset this.

They say the rise of China as an economic superpower has been the dominant story of the past 30 years. It led to a global influx of hundreds of millions of workers. These cheap workers help fuel the rise in supply of goods for companies around the world. Along with favourable demographics, it resulted in increased economic output and lower inflation growth across developed market economies.

The authors think China’s largest contribution to global growth is now past as its working age population is shrinking, as its people grow old. And the West is witnessing sharp declines in fertility rates, continued increases in life expectancy, and falls in growth rates of working age populations. This means the ageing of populations everywhere, barring Africa.

Also, the dependency ratio – the ratio of those who need support because they do not earn income relative to workers – is worsening. The populations of most countries will go on rising for the next 25 years because the number of old will offset the number of young. But between 2045 and 2050, the global population will begin to decline.

The authors say this decline will lead to labor shortages and upwards pressure on wage rates, which will be reinforced if taxes on workers increase to pay for welfare for the ageing. That will fuel structurally higher inflation and higher nominal interest rates (but not necessarily real rates).

It will lead to employers increasing investment because labor will become more expensive. That will improve worker productivity, but it won’t be enough to counter the declines in the working age population.

The book doesn’t consider technology as a major factor in declining inflation rates in previous decades and they play down its potential role in future. To critics that mention Japan as an example for ageing populations not leading to inflation, Goodhart and Pradhan argue that Japan’ situation happened against the backdrop of China’s rise and that rise explains much of the low inflation that Japan has experienced since.

They also mention that immigration can help offset ageing populations in some countries. They say the issue of immigration is partly to blame for the rise of populist parties in recent years. The authors believe it’s also divisive because it pits mainstream economists, who largely welcome immigration, against the public, which wants it restricted.

Impact on super and the Age Pension

As Australians live longer, it will also put enormous pressure on welfare budgets. Governments will need to raise money to pay the bills. And they’ll pick politically easy targets to achieve this.

For example, negative gearing is political dynamite, and the Federal Government will avoid tinkering with it unless forced too.

On the other hand, super and the pension are easier targets. This year, we saw the introduction of a new tax on super balances over $3 million. Given future pressure on budgets, further changes to super seem inevitable.

That isn’t to say that super isn’t a good vehicle to build wealth. It currently is. Though whether it remains the case is an open question. Making sure that you have diverse investments outside of super to fund your retirement would seem prudent.

As for the pension, it used to be seen as a ‘right’ but is now perceived as welfare. In recent years, the Government has tightened criteria for the pension. More tightening seems a given. In future, a generous pension is far from guaranteed.

All of this suggests that people need to think carefully about how to they best accumulate wealth to fund their retirements.

Morningstar

Morningstar