Large superannuation funds are increasingly insourcing investment management responsibilities. And many of these funds now feature on many advisers’ approved product lists. The FASEA, or the Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority, place the onus firmly on advisers to recommend investment products in good faith and with competence. So why is this trend of insourcing investment management a relevant consideration for advisers? A high level of diligence and ongoing monitoring is crucial, as the insourcing trend adds an additional layer of complexity.

Many large industry funds are moving from a model whereby assets under management are outsourced to external managers (normally under the guidance of an asset consultant) toward a model where investment management expertise resides in-house and assets are managed directly by staff members of the super fund. This trend has emerged over the last decade and is certainly not exclusive to Australia. For example, Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (a large Canadian pension fund) manages 80% of its AUD 250 billion of assets in-house (as of 30 June 2021). In Australia, the degree of insourcing varies by fund and asset class and typically a hybrid model is in place with investment management duties shared between internal and external teams. Morningstar recently reviewed some of the larger industry funds, including AustralianSuper and CBUS, and they both have a hybrid model in place. At AustralianSuper, approximately 44% of assets are managed internally by around 200 employees, and 37% of assets are run internally at CBUS by 115 investment staff.

Assessing the Risks and Benefits

Let’s look at some of the pros and cons of insourcing investment management and where the complexity creeps in. The benefits include increased control of the total portfolio and expected lower overall fees to members. Some factors to be aware of are the investment performance of the internal team; the investment talent attracted and retained within the fund; how a team is managed and, if required, replaced; and the transfer of risk that occurs with internalising investment management.

In-house investment management provides considerably more control, as the fund is better able to respond quickly to market movements at a total portfolio level and integrate environmental, social, and governance considerations at every point in its investment process. Further, large funds looking to place money with external managers can face capacity issues–the external manager won’t manage the required amount for the super fund due to the business risk of a single large client or the potential alpha diminution from managing too much. Finally, owning scarce assets (think Sydney or Heathrow airports) directly also can be very attractive for these long-term asset owners. It often supports a much longerterm ownership horizon than if the super fund invests through an external investment manager who is managing a fund with a 10-year (or less) time horizon and needs to buy and sell the asset within that time frame.

Scaling Up and Fee Costs

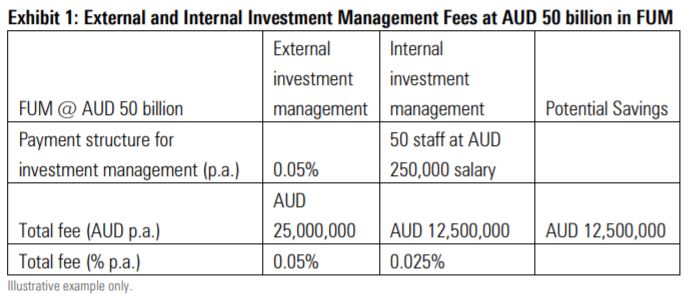

Lower fees have been high on the agenda for Australian investors for years and insourcing investment management can generate fee savings for investors. AustralianSuper1 estimates that its internalisation programme now saves members around AUD 200 million annually. The fee savings are generated through two main mechanisms. The first is a result of substituting the payment of asset-based fees to external managers for largely fixed salaries to internal staff. Let’s take a relatively extreme example: If a large fund has an equities allocation of AUD 50 billion and it pays, on average, 5 basis points per year to an external manager, it is paying away AUD 25 million per year in investment fees. The other option could be to pay 50 people an annual salary of AUD 250,000 each and reap some cost savings.

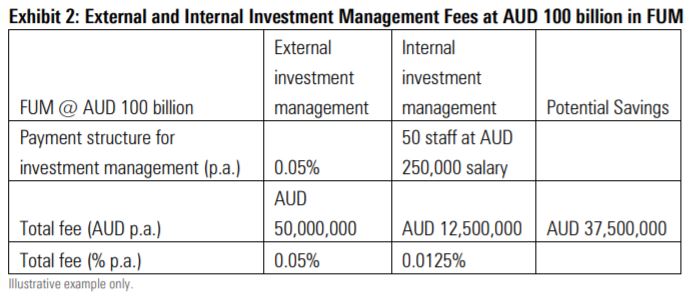

The magic is when additional scale is introduced and the AUD 50 billion of equities grows to AUD 100 billion. It is unlikely that a significant increase in staff numbers is required to manage these additional assets, and unless the 5 basis points of external investment management fees tiers down to 0 basis points, there are significant fee savings potentially available. Clearly in practice it is always a balancing act to ensure adequate resources are in place to continue to scale internal investment programmes and generate optimal outcomes for members–but the potential scale benefits are real. And this relatively extreme example highlights why AustralianSuper estimates it is banking large savings for members given the portion of its internally managed assets.

The other part of the equation is performance fees. Many private equity, infrastructure, property, and alternatives investment managers command lucrative performance fees for performance in excess of a benchmark. While in-house investment personnel may earn performance-linked incentive payments, they are often much lower in absolute terms and linked to the overall fund performance, which creates a better alignment with members.

Fee Savings and Poor Performance?

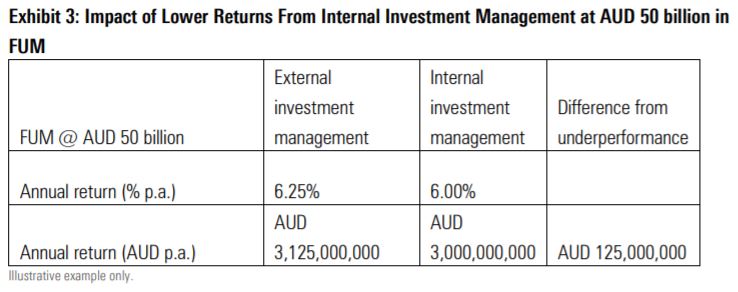

While the fee savings available from in-house investment management appear dazzling at first blush, it’s worth considering how quickly these fee savings could be eroded by poor performance. Investment management is a tough game and, unless roughly equivalent levels of competence can be achieved, the potential loss from lower investment returns can quickly swamp any fee savings. Returning to our simplified example from above, at AUD 50 billion in assets, annual underperformance of just 25 basis points results in AUD 125 million of lost capital for members. And while the fund may be able to publish a lower investment management fee, investors eat net returns. This is a key reason why many funds are selective about the asset classes they insource–they want to internalise strategies where equivalent levels of competence with external managers can be achieved, and that is not necessarily achievable in every asset class.

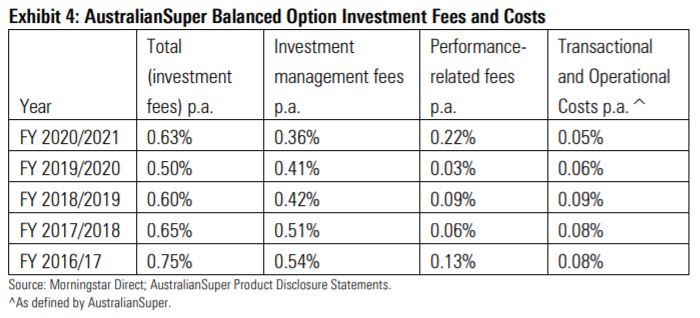

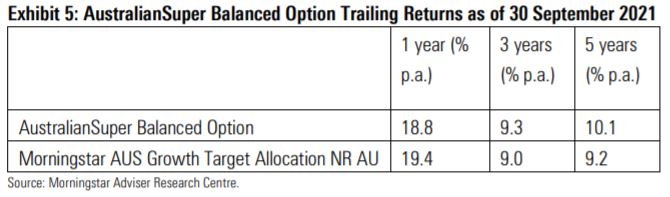

So, what are the results? Let’s use AustralianSuper as the case study. It has successfully lowered investment management fees for investors (refer to the second column “Investment management fees” in Exhibit 4) and delivered solid investment returns (refer to Exhibit 5) for members for the last five years. Based on the return data publicly available, it is impossible for us to know whether a fully outsourced model would have delivered better returns to investors, but prima facie members do not appear disadvantaged by the model.

People and Governance

People are a vital pillar to any successful investment management business and are a key ingredient to funds achieving equivalent levels of competence with external managers. A deep dive into the people in the investment management team, the super fund’s culture, and its remuneration practices is necessary to determine whether the fund has a fighting chance to deliver equivalent returns to an external manager and whether the right investment people are likely to be retained within the fund. Funds know that retention will be a key challenge–the lure of higher salaries and equity participation at external

management firms is real.

The importance of good governance when insourcing investment management should not be underestimated. Internal investment teams need clear objectives, and performance should be measured periodically by both the trustees of the fund and independent assurance reviews. It’s difficult to evaluate investment decision-making over the short term, and it may take years to properly assess whether the internal team is delivering on its objectives. This begs the question of what happens when the internal team is not delivering to its objectives and needs to be terminated? Hopefully this has been

contemplated by the trustees prior to insourcing and a clear plan is already in place–as it is not as simple as replacing one external mandate for another and raises a host of issues, including costly redundancy payments and internal cultural disruption.

Finally, insourcing investment management is a transfer of risk–funds reduce agency risk (such as the risk that external managers are benefitting themselves at the expense of the fund’s members) for a number of other risks. Besides the risks outlined above, investment-process-related and operational risks should not be underestimated. The integration of internal and external management into a coherent investment process should be scrutinised carefully. And the supporting infrastructure required to adequately manage money is expensive to set up and can be costly for investors if not done well. External managers have often spent years refining their trading, compliance, technology, and back-office support systems. Internal teams need the same infrastructure, and trustees need to carefully oversee this part of the equation. After all, the contractual protections that come from external management no longer exist, and losses resulting from a large trading error will now be compensated by the fund’s own insurances or its reserves.

There’s a lot to like about insourcing, but it is not for every fund and investors should be aware of what can go wrong. For advisers to recommend one of these investment products in good faith and with competence means understanding the inherent complexity inside these behemoths. While Morningstar holds some of these large super funds in high regard, considerable time is dedicated each year to reviewing the people, processes, parent, price, and performance of large superannuation funds. These funds are anything but light touch from a due-diligence perspective.

1 2021 AustralianSuper Annual Report

Morningstar

Morningstar