Warren Buffett’s annual letters to Berkshire Hathaway (NYS:BRK.A) shareholders are always invaluable. They contain some of the most insightful, timeless and entertaining investment wisdom money can buy, yet you don’t need to pay any to read them. The 2023 edition was particularly profound, published on February 24, 2024, three months after the passing of Buffett’s lifetime investment partner, Charlie Munger. In likely the first annual letter since 1977, penned without his curmudgeon sounding board, Buffett paid Munger the ultimate tribute.

He credited Munger as the “architect” of the present-day Berkshire and thanked him for fundamentally changing Buffett’s investment mentality, from one scouring for so-so companies trading at dirty-cheap prices, to one obsessed with “wonderful businesses purchased at fair prices”.

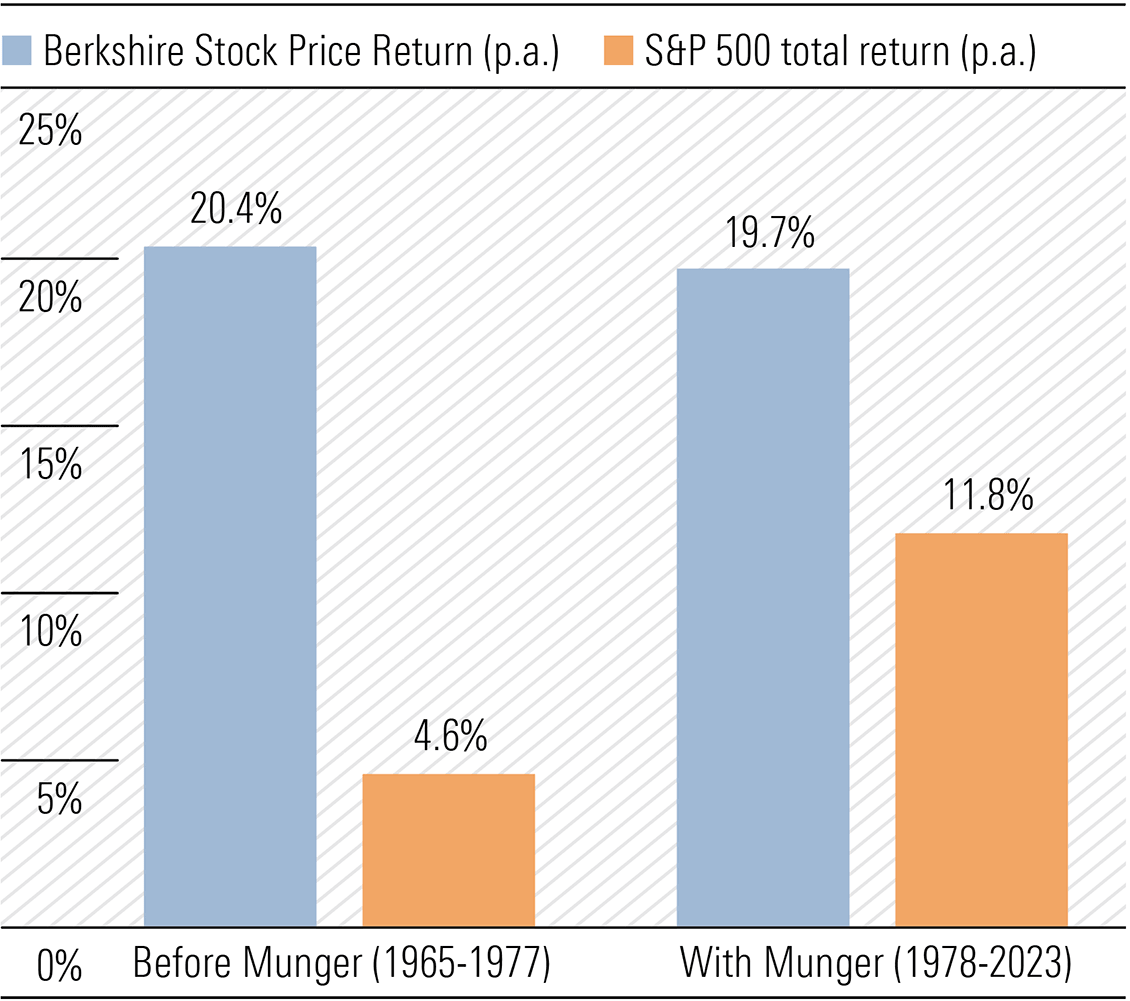

Buffett, of course, was being modest. He did pretty well by himself before Munger joined him in 1978, with Berkshire generating compound annual average return of 20.4% from 1965 to 1977, easily exceeding the 4.8% returned by the S&P 500 index. Even before Munger started badgering him about buying quality, Buffett appreciated the appeal of investing in “truly outstanding” businesses.

Exhibit 1: Berkshire shares outperformed market, both before and after Munger joined

Source: Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter 2023, Morningstar Direct

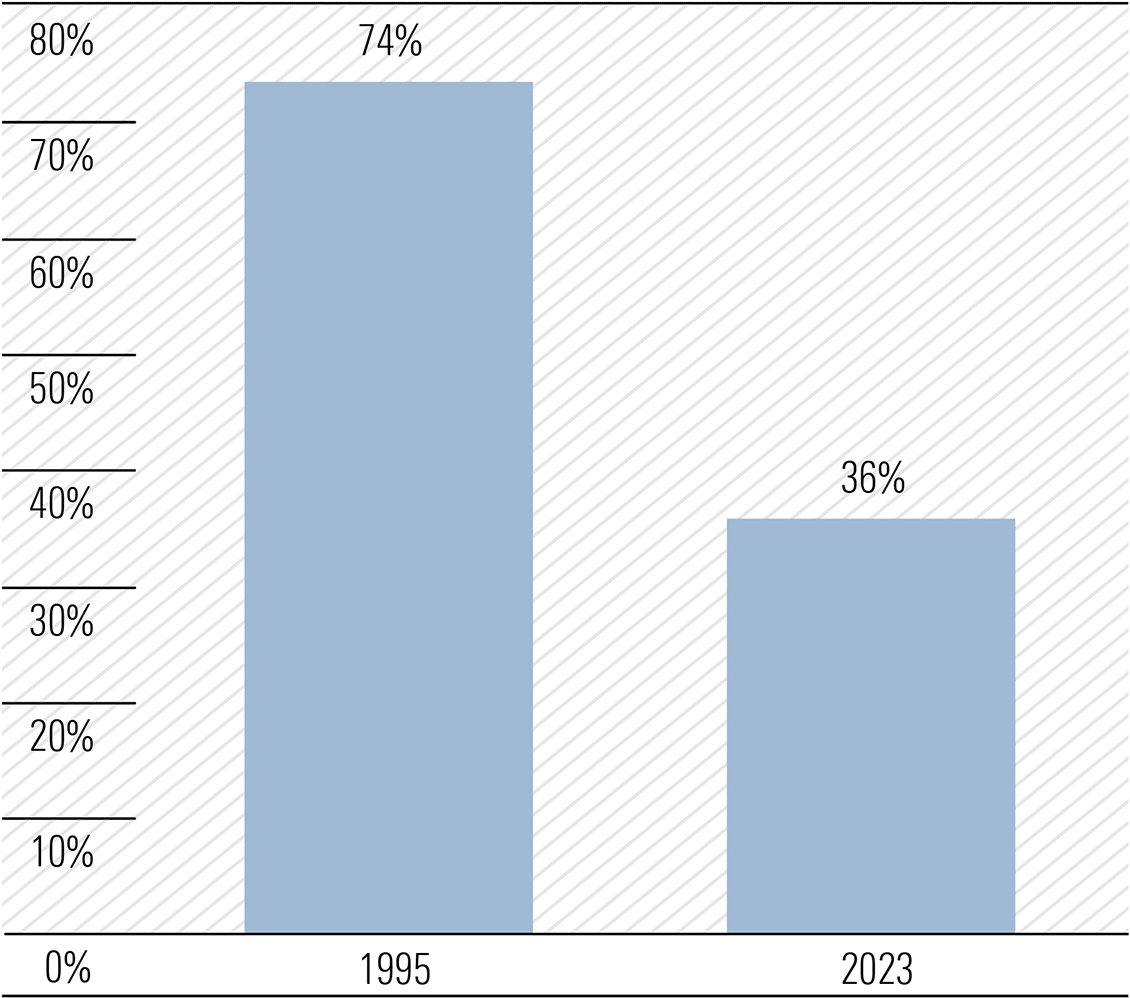

However, after Munger came into Berkshire in 1978, the annual letters increasingly emphasised the advantages of investing in businesses with attractive economics and durable competitive edge. They used Berkshire’s own purchases as real-time examples of what those qualities look like. And when those qualities kept shining through, Berkshire couldn’t get enough of them. So, it started swallowing up these companies whole (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Decreasing percentage of Berkshire assets held in minority investments

Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2023 Annual Report

The stock price performance of Berkshire since Buffett and Munger formally joined forces from 1978 speaks for itself. As Exhibit 1 shows, after Munger joined, Berkshire shares have returned 19.7% a year on average from 1977 to 2023−an amazing track record of outperformance against the market, especially with the company’s net assets ballooning from USD 142 million to USD 561 billion. Exhibit 3 shows the entirety of Berkshire’s stock price performance since 1965.

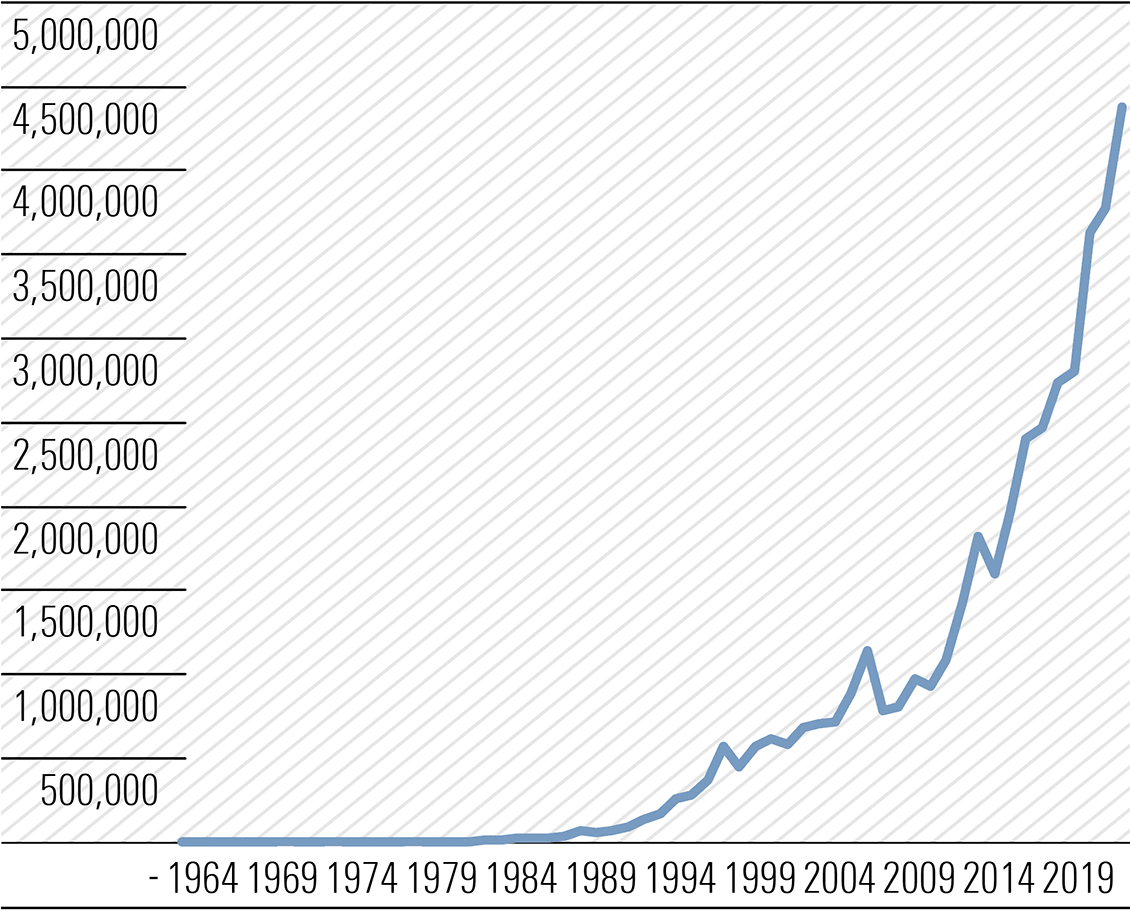

Exhibit 3: Value of USD 100 invested in Berkshire in 1965 reached almost USD 4.4 million by end of 2023

Source: Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter 2023, Morningstar Direct

We make three observations about Berkshire’s performance track record.

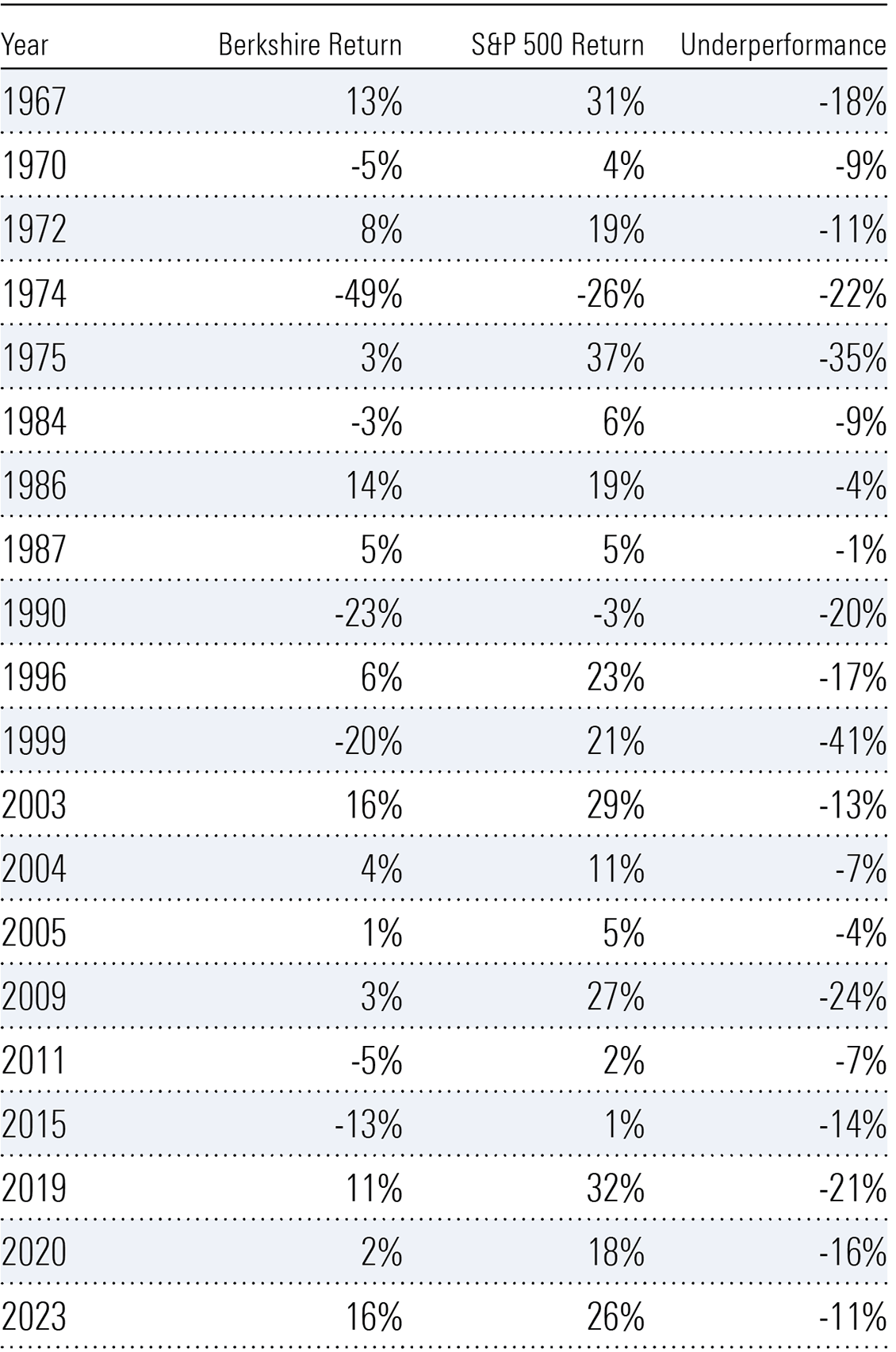

Firstly, it has had its ups and downs. Notably, it was down 49% in 1974, 23% in 1990, 20% in 1999, 32% in 2008 and 13% in 2015. Relative to the S&P 500 index, Berkshire shares also underperformed in a number of years, as can be seen in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4: Years where Berkshire underperformed market

Source: Berkshire Hathaway Annual Letter 2023, Morningstar Direct

During these lean years, there was no shortage of doomsday prophesies about Buffett/Munger’s investing prowess. Impatient investors, influenced by the negative noise and criticism, likely pulled out of Berkshire.

For instance, I still remember the schadenfreude permeating the market when Berkshire shares dropped 20% in 1999 while the S&P 500 was up 21%. Market commentators and “smart money” questioned whether the ageing Berkshire duo had lost its touch amid a technological and dotcom revolution. Since then, Berkshire shares have returned 10% a year on average compared to 7% for the S&P 500 index.

Even now, there is a plethora of articles pointing to the underperformance of Berkshire shares since the start of 2019, up just 12% versus S&P 500’s 16% gain. However, since all the way back to 1965, Berkshire shares have returned a compound annual growth rate of 20% versus S&P 500’s 10% over the same period. It means USD 1 invested in Berkshire in 1965 is now worth USD 43,749, considerably more than the USD 309 that would have been if the same dollar had been invested in the S&P 500.

The magic of compounding is such that, even from 2019 when Berkshire has been underperforming, your USD 1 investment in 1965 would have begun 2019 at USD 24,660 and ended up USD 43,749 at the end of 2023—a gain of USD 19,088 at the “inferior” 16% average annual return. In contrast, your USD 1 investment in S&P 500 in 1965 would have begun 2019 at USD 149 and ended up USD 309 at the end of 2023—a gain of USD 160, even at the “superior” 16% average annual return. I know which one I would prefer.

Our second observation is exercising patience and letting the magic of compounding snowball our savings to prosperity is easier said than done. Emotions get in the way and there are infinite temptations in the market, forcing us to “don’t just sit there, do something!” Indeed, the primary function of the gazillion pieces of information, news, rumours, musings and analysis propagated every day is to compel financial market participants to act, react and create transactions. But patience has paid handsomely for long-term Berkshire shareholders.

Buffett’s younger sister, Bertie, certainly tried to be an active participant in the market in her early days. According to Warren, it wasn’t until 1980, when Bertie was 46, that she decided to stop mucking about and just passively watched her money in a mutual fund and Berkshire shares grow. If she invested USD 100,000 (purely my guess) in her brother’s company in 1980, that would have grown to … wait for it … over USD 100 million by the end of 2021. No wonder Bertie was able to donate “nine-figure” philanthropic gifts. And I bet she has never listened to any self-proclaimed “super investors” on twitter, flogging the next great investment trade!

Our third observation circles back to the investment tenet Buffett credited Munger for instilling in the Berkshire Hathaway Way—invest in companies with “mouth-watering” economics. It is this tenet that has turbo-charged the magic of compounding for Berkshire shareholders.

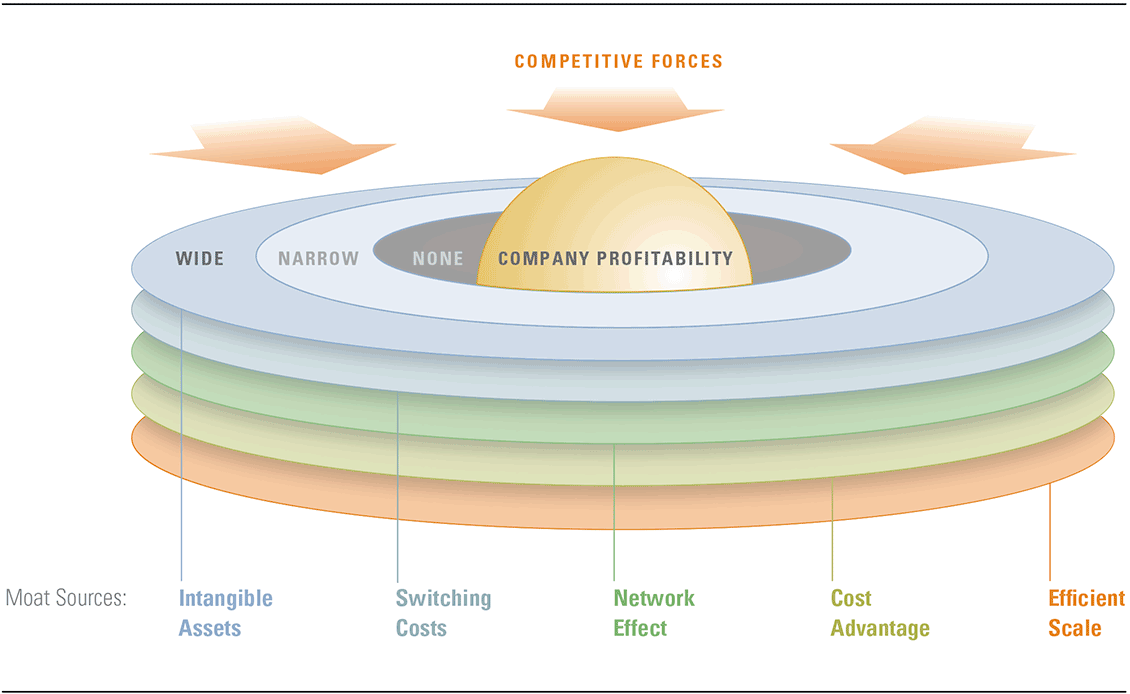

In layman’s terms, “mouth-watering” economics mean quality companies. But “quality” can be such a broad and nebulous attribute. We at Morningstar have tried to define this tenet in our economic moat framework, one that guides and governs the way we look at all the companies under our coverage. And, of course, we are indebted to Buffett for coming up with this allegoric principle, as he was really the first investor to coin the term, economic moat, during the 1995 Berkshire annual shareholders meeting.

In essence, we see a quality company as one that can generate returns on their capital at a sustainably higher rate than the cost of that capital. In a laissez-faire economy where capital freely flows to the best available returns, generating such excess returns is difficult. Yet, some companies have been doing so, and are likely to continue doing so, for a very long time. We at Morningstar have identified five ways or sources that can furnish an economic moat around a business, so that it can fend off competition and continue to generate excess returns. Exhibit 5 illustrates these five sources.

Exhibit 5: The five sources of Economic Moat

Source: Morningstar

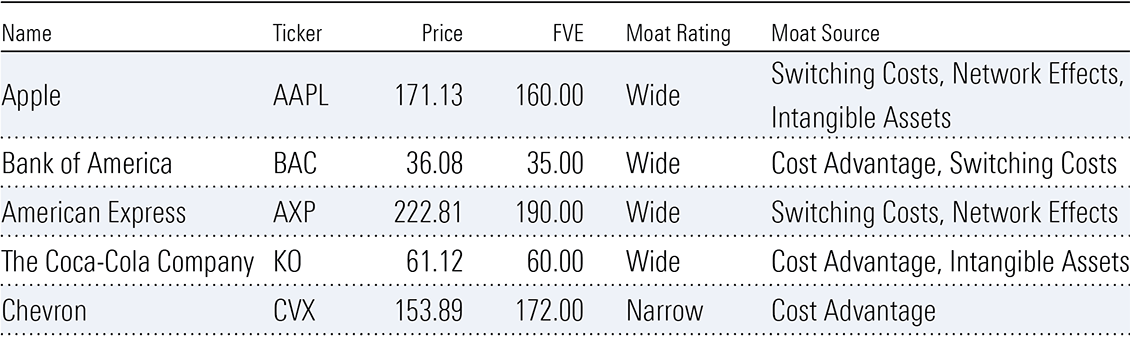

To see a real-time application of this moat framework, take a look at Berkshire’s current top-five equity holdings, as shown in Exhibit 6. Buffett and Munger have over the years explained why they laud the economics of some of these companies. They like Coca-Cola Co (NYS:KO) because they cannot envisage the power of its brands diminishing. In fact, they are likely to increase even more in the future, as the brands are exported overseas and new markets open up for Coca-Cola’s “fun-loving” syrup. In the Morningstar framework, we view that brand power as an Intangible Assets source for an economic moat that is likely to protect Coca-Cola’s excess returns for a long time to come. For American Express (NYS:AXP), Buffett believes consumers and businesses’ “need for unquestioned financial trust” plays right into the global group’s wheelhouse. But, according to our analyst, it is not American Express’ brand reputation that is the source of its economic moat. Rather, it is the group’s closed-loop network for cardholder payments, coupled with its huge ecosystem of affluent customers and merchants keen to access those customers, that erect network effects and switching costs to maintain American Express’ excess returns.

Exhibit 6: Berkshire’s five largest equity holdings and our view of their Moat sources

Source: Pitchbook, data as at close of market on March 13, 2024

Such are the “mouth-watering” economics of these businesses, the five stocks shown in Exhibit 6 constituted 79% of Berkshire’s equity portfolio at the end of 2023. Instead of “diworsifying”, Buffett and Munger believe when you’re on a good thing, don’t just do something—sit there and watch the few eggs in the one basket very carefully. For us mere mortals, perhaps this is taking too far and some diversification is sensible.

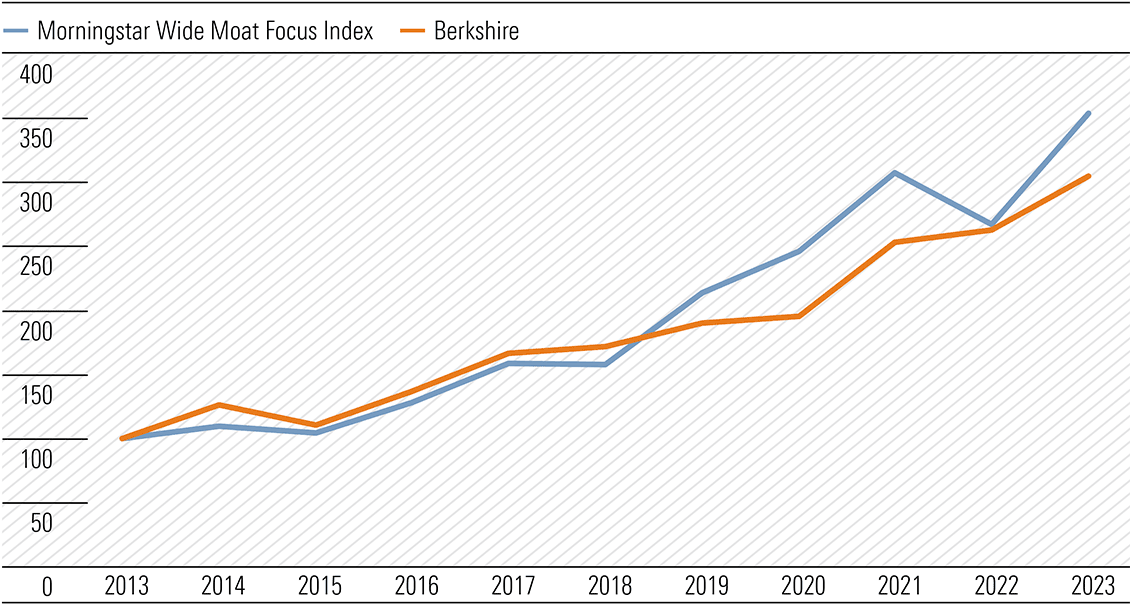

We are believers in the Berkshire Hathaway Way of thinking about companies. And we are believers in the magic of compounding once we are invested in these quality companies. So much so that we even have a family of Morningstar Moat index funds.

The flagship fund is the Morningstar Wide Moat Focus Index which provides investors exposure to a diversified portfolio of around 50 attractively priced US companies with durable competitive advantages according to Morningstar’s equity research team. It is a fund with almost USD 16 billion of assets under management, and has outperformed the US market by 3.3% per year since its inception in February 2007. In fact, the performance of Morningstar Wide Moat Focus Index has gone toe-to-toe with Berkshire over the past ten years to 2023, generating an average annual return of 13.5% compared to 11.8% for Berkshire (see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7: Morningstar Wide Moat Focus Index going toe-to-toe with Berkshire

Source: Morningstar, Morningstar Direct

Buffett is indebted to Munger for influencing his way of thinking about companies, in terms of their durable competitive advantages. We at Morningstar are even more indebted to this Berkshire dynamic duo, for the way we think about the sources of durable competitive advantages.

Berkshire Hathaway annual letters and the pearls of wisdom from the subsequent annual shareholder loolapalooza in Omaha will not be the same without Munger. But his contribution to Berkshire’s performance and Buffett’s investing philosophy will live on, as will his many enduring quotes. We end with one of the Munger classics:

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent”.

Morningstar

Morningstar