Introduction

The performance of equities markets in 2019 was one of the best for decades. 2020 was the year when several records were broken. New peaks were achieved early in the new year; the fastest bear market (-20%) in history in March; the fastest run to bull territory (+20%) between April and May; and the best November performances for many global markets, with new all-time highs being registered in US markets.

It was a year of trials and tribulations, where patience was tested but those in for the long haul were ultimately relieved and rewarded. Late March provided some rare opportunities for those with cash. Investing is a test of endurance and 2020 proved to be one of the most challenging in many decades. Despair and then euphoria.

2021 is unlikely to be a repeat. Markets could begin the year with an extension of the current upswing, but as it unfolds several questions will undoubtedly be asked about the progress of the economic recovery and the relationship to risk asset valuations.

In early 2020, the first signs of a truce emerged in the trade war between the US and China with the signing of the Phase One deal. Tariffs were rolled back, China promised to expand the purchase of US goods and agricultural produce and commitments on technology transfer, intellectual property and currency were at least partially addressed. The level of uncertainty subsided, and global financial markets surged as central banks’ “lower-for-longer” interest rate policy combined with quantitative easing swelled an already brimming ocean of liquidity.

Global liquidity has reached levels not previously entertained as the relatively quick succession of trade wars, slowing economic activity and a pandemic and associated recession saw an “on the run” response from central banks. “Cut interest rates and throw money at it” was the prescription despite the different ailments. Predictably, most of the liquidity created has been misdirected. Global business investment has disappointed, with risk assets the major beneficiary of central bank largesse. This must be frustrating as bubbles begin to appear, particularly in equity markets. This is somewhat akin to demand-pull inflation, where too much money is chasing too few goods, and prices rise.

Employment or unemployment will be one of the great challenges of 2021. Unprecedented job losses across developed economies are unlikely to be fully restored and this will add pressure to household income. The knock-on effect is subdued, rather than buoyant economic activity, given private sector demand is dominated by household consumption. Corporate profitability is also dependent on robust private sector demand.

The new year will launch off an elevated platform for market indices. All US indices are currently at or near record levels. Expectations are sky high as investors ignore any semblance of bad or disappointing news. The US November jobs report was a classic example. Despite non-farm job creation of 245,000 meaningfully missing expectations of 460,000, investors were heartened the disappointment may, not will, ultimately force warring Democrats and Republicans to a stimulus deal which is now in its fifth month of negotiation. Hope springs eternal, but as share prices continue to rise, so valuations become even more stretched and therefore exposed and vulnerable to disappointment.

Other global markets are also elevated, most within 10% of their respective high-water marks and while momentum is still positive, failure of economies to respond to the availability of a vaccine in a sustainable manner could quite easily trigger a correction of 10% plus. Widespread vaccination will be the key to halting the virus. There has already been some discussion around the possibility of a “double dip” recession in the US as the rate of new infections surges to new peaks with the onset of colder weather in the northern hemisphere.

In most markets, a fully-fledged recovery is already priced in. Debt levels are off the chart. Central bank action is encouraging risk taking on a wide scale and equity investors are embracing “there is no alternative” (TINA) mantra while ignoring skinny low risk-adjusted returns. These returns are relative to low risk-free bond yields. I am not convinced bond yields will remain corralled at current levels indefinitely, as many predict. There is movement at the station already.

Frustrated central banks may consider the validity of yield curve management via asset purchases. They may also finally recognise that essentially underwriting zombie risk is unproductive and delivers diminishing returns in terms of economic activity and job creation. The weak corporates dampen productivity and generally abuse resources, especially liquidity at an unbelievable price.

In the wake of the pandemic, technology stocks led by the FAANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) + Microsoft, have sent global technology indices into orbit. Huge changes in social and business behaviour triggered a massive increase in demand from stay-at-home/remote working consumers to update home offices and entertain increasingly bored children. Much of this pull-forward demand for office hardware and entertainment services, driven by necessity, is unsustainable as restrictions are lifted and open air and space become accessible. Otherwise start researching optic and eye health companies as retinas and pupils are damaged and macular degeneration spikes from over-exposure to computer, iPad and iPhone screens.

If there was one stock which emulated the saying “out with the old in with the new” it would be Tesla. As it joins the S&P 500, its market capitalisation is over US$600bn which is greater than the combined capitalisations of Ford, General Motors, Volkswagen, BMW, Fiat Chrysler, Toyota, Honda, Nissan and Hyundai. That does appear somewhat excessive and a sign of the times. Perhaps a reality check is in order.

Australia – Seeking normality as recession passes

Australia is desperately seeking a return to normality. Being an island continent, Australia had a much better chance of controlling coronavirus than both the US and Europe. Despite the cold climate, Antarctica was also successful. But getting the economy back on a

sustainable path to full recovery will be much more challenging. While the availability of a vaccine will assist the process and provide more certainty, the behaviour of the corporate sector in terms of job creation and investment will be critical. Households have done the heavy lifting within the private sector over the past decade and now require meaningful support given household income growth will remain well below trend for some time as wages growth basically flat lines as support programs are withdrawn.

The Reserve Bank’s (RBA) monetary policy is locked in, laser-like, on employment and inflation. The trend in both these sensitive economic benchmarks will determine the longevity of a cash rate at 0.10% (10 basis points). Governor Philip Lowe says the board “is not expecting to increase the cash rate for at least three years” and “is prepared to do more if necessary” in terms of the size of the asset purchase program (quantitative easing). These are very definite statements, and it will be interesting to see what events trigger a blink of the eye.

The clear priority of fiscal policy has been to restore the million plus jobs lost earlier in the year. The Seeker/Keeper support programs were very successful in stemming the losses and importantly shoring up household income. In the June quarter the total number of jobs fell 7% or by 1.028 million and hours worked fell 9.8%. In the four months ended October, 375,000 jobs, or 36.5% of those lost, were restored still leaving a void of just over 650,000. The closing down of the Victorian economy will impact November’s reading, its reopening supporting December’s. But the long haul is ahead with company management still proving cautious in adding to the workforce while others are still trimming. Despite the reopening of domestic borders, Qantas is still cutting, so are financial services. It is likely unemployment will stay above 6% throughout 2021 and underemployment above 10%. The October participation rate increased to 65.8% adding upward pressure on the unemployment rate and we may see January’s 66.1% record challenged.

Inflation remains subdued and well below the RBA’s 2%-3% target range. Markets are convinced inflation will continue to hibernate for years. The RBA’s prediction on the cash rate being unchanged at 10 basis points until 2024 also coincides with that conviction.

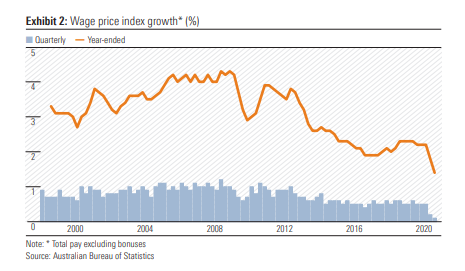

The RBA will be hoping employment growth and tax cuts will support household income and combined with elevated savings and a seven-year high in consumer sentiment, will underpin growth in household consumption. Offsetting this will be the withdrawal of Seeker/Keeper income support programs and below-trend wages growth as unemployment remains above 6%. The conditions for demand-pull inflation are not evident given excess capacity exists across most of the economy. (Exhibit 2)

The stronger than expected GDP growth of 3.3% in 3Q20 was driven by household consumption, particularly of services (+9.8% and goods +5.2%). After a 12.5% contraction in 2Q20, household consumption rebounded by 7.9% in 3Q and with the reopening of the Victorian economy, further growth is expected in 4Q. With the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Index of Consumer Sentiment hitting a 10-year high in December, together with an iron ore-driven positive contribution from net exports and continued strong public demand (infrastructure spending), GDP growth of 2%-2.5% is expected in 4Q. The contraction for 2020 is likely to be just over 2%.

Growth between 3% and 3.5% is expected in 2021, suggesting Australia’s GDP will recover the lost ground in 2020, perhaps by 2Q21 but certainly by 3Q. But the onus will be squarely on the household and therefore employment, which is still tenuous. The iron ore price is likely to pull back from current elevated levels, weighing on the contribution from net exports. We will need to see an upturn in credit demand (financial aggregates) for both housing and business from the well-below trend levels currently being recorded, as these are meaningful drivers of economic activity.

China is an integral part of Australia’s growth forecasts. Should the current spat escalate as Chinese commercial aggression breaks new ground, downward revisions may have to be addressed. Clearly Australia has an over reliance on China and this concentration risk should not be ignored by government or investors. On-shoring is not the answer given the yawning gap in wage rates.

The A$ is likely to continue to strengthen against the US$, as the latter weakens.

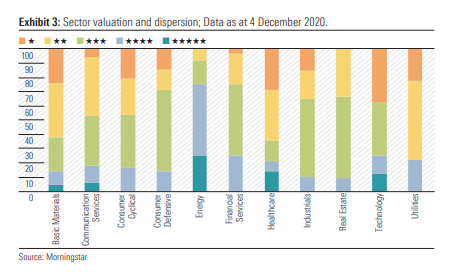

At current levels we view the market as moderately overvalued. The average unweighted price/fair value estimate ratio of our coverage is 1.14, while the cap weighted average is 1.26. The most undervalued sector is Energy with a median P/FVE ratio of 0.70 and a cap weighted ratio of 0.77. The most overvalued sectors are Retail and Metals & Mining with median P/FVE ratios of 1.38 and 1.36, respectively. (Exhibit 3)

United States – somewhat of a misnomer

Hark back to the time Barack Obama returned the Democrats to the White House winning the presidential election in November 2008 and taking control on 20 January 2009. The transition was relatively seamless. Civil unrest was virtually absent.

Back to the present, and hopefully not far into the future. The US is now facing acquisition and transition risk. Acquisition risk as the Democrats have acquired the White House and transition risk given the width and depth of the social divide within the country. Donald Trump becomes the first one-term president since George H. W. Bush (1989-1993) and it does not sit well with him or over 70 million voting Americans.

The global outbreak of coronavirus has brought recessions to most of the developed world economies, predominantly the US and Europe. The combination of an economic shock of record-breaking proportions and widespread social disruption means the fracture is not clean, but compound. It will take much longer to heal, but financial markets continue to ignore longevity risk at their peril.

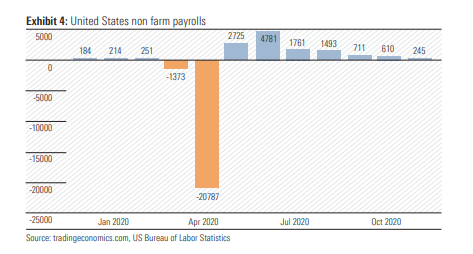

Starting with employment and unemployment, the challenges will be meaningful and testing. In March and April 22 million American jobs were lost. Since May the economy has clawed back 12.3 million and there are at least 10.7 million still unemployed. While coronavirus infections surged to new peaks in November, resulting in renewed shutdowns and restrictions, the loss of traction in the jobs market must be of concern. President-elect Joe Biden used colourful and provocative adjectives, describing the November jobs report as “grim” and warning of a “dark winter” ahead if Congress did not pass the relief bill. Will they be enough to budge the Republicans into a deal before his inauguration on 20 January? (Exhibit 4)

The Federal Reserve (the Fed) will continue to support the economy by ensuring the financial system is well greased with enough liquidity to allow efficient and effective operation. But the liquidity created will also support risk asset markets and risk taking. With the change of residents in the White House, chairman Jerome Powell’s life will be more settled. The appointment of the dovish former Fed chair Janet Yellen to the post of Treasury Secretary is likely to see a more cohesive approach to monetary and fiscal policy, sadly lacking over the past four years.

However, despite being on the same page Powell and Yellen face an unsettled and uncertain environment which is likely to prove quite testing for some time. 2021 will not be a “walk in the park” domestically or internationally for the Biden administration. With 10 million jobs still to be restored, and the pandemic far from under control a vaccine can’t come quick enough. But the anti-vaxx movement is alive and well and a new vaccine gives them the opportunity to fly their flag.

The level of social discord is also of concern especially when the country needs cohesion and solidarity. Growing inequality of income and wealth does not make unification easier. Monetary policy is widening the gap and coronavirus has only revealed its extent. The

healthcare system is also letting the lower socio-economic segment down, adding to the frustration and raising the bitterness. The president-elect had better have plenty of answers over the next four years as many questions will be asked of his West Wing.

While the possibility of a “double dip” recession has been aired, it is unlikely. After the 33.1% GDP growth in 3Q20, US GDP remains well below (15%) 4Q19 pre-pandemic levels. A virus ravaged fourth quarter is expected to restrict growth to below 5%, suggesting it will be at least 2Q21 before GDP returns to pre-pandemic levels.

The US$ is likely to remain under pressure through 2021 swamped by the money printing of the Fed. Its purchasing power is being diluted with not a hint of inflationary help.

China – robust recovery continues into 4Q20; sustainability the key question for 2021

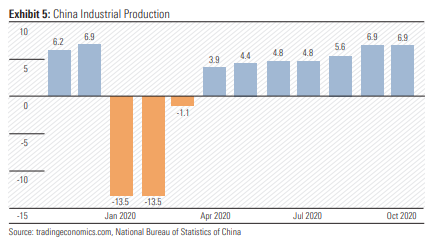

Can the Chinese economy keep expanding at twice the rate of developed economies through 2021? The post-pandemic recovery momentum has continued into 4Q with factory output surging and domestic demand reigniting. GDP growth was restored after one quarter’s contraction. (Exhibit 5)

The 14th Five Year Plan (FYP) (2021-2025) will be revealed at the National People’s Congress in March. These plans are the most important single guiding document outliningthe strategy and policy direction for both economic growth and social development. The central committee of the Communist Party met in October and subsequent plenum documents have indicated little change in the overall policy direction. But there are signals of subtle changes and the dual circulation policy (DCP) will play a decisive role in the 14th FYP.

The DCP, first mentioned in May, lifts the focus of the domestic market or internal circulation. It is a strategic blueprint for the country and its economy to adapt to increasing instability and hostility in the global environment. The first airing was before Biden ousted Trump and it was clear China was determined to become more self-sufficient with president Xi Jinping stating China would “gradually form a new development model in which domestic circulation plays a dominant role.” The DCP is likely to see China reduce its export-driven strategy or external circulation, which has been very successful in elevating its position to the world’s second ranked economy, but without its abandonment.

Replacing high-speed growth with high-quality growth is on the agenda. This perhaps suggests a reduced focus on infrastructure and export growth and a refocus on internal growth. The outsized spending on infrastructure has resulted in diminishing returns in real economic terms in more recent times. We may witness peak demand for iron ore and metallurgical coal from China in 2021.

Security of supply chains in a an increasingly hostile global environment will also have priority. The DCP will address these issues and Made in China 2025 policy launched by president Xi Jinping in 2015 will be reinforced to satisfy dual goals of developing domestic capacity while pursuing global market opportunities. Supply-side structural reform will help in rebalancing the economy.

An increased focus on innovation, technological independence and self-reliance will see a continuation of the transition from cheap-low tech products to high-end and specialised production. This will satisfy the goal to “tech self-sufficiency”.

Despite all stops being pulled out in the final quarter of 2020, China will fall marginally short of its plan to double the nation’s GDP between 2010 and 2020. The miss so close it can be classified as a statistical error. Clearly, China has dominated the global scene over the past decade, with economic growth far surpassing any developed nation. Australia’s iron ore and coal companies have been major beneficiaries of almost continuous stimulus programs since the GFC. That is unlikely to continue.

GDP growth of between 5% and 6% is likely for 2021.

Energy – OPEC and OPEC+

There are currently 23 members within the OPEC+ block of oil producing nations. OPEC+ is a loose amalgam of the core block of 13 genuine OPEC members including Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Nigeria and Iraq among others; and the 10 “plus” member states including Russia, Mexico, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan etc. Over the past five years OPEC+ members have accounted for an average of 50.6 mmbpd or just over 60% of global oil production, excluding natural gas liquids and biofuels. So, it is a useful block with which to manage oil prices, particularly when members adhere to set production quotas.

Or it should be. The fly in the ointment is US shale. While OPEC+ member production essentially held steady over the past five years, US oil production increased by 40% to 12.2mmbpd. And that doesn’t include US natural gas liquids output, which increased by 60% to 4.8mmbpd. OPEC is between a rock and a hard place. It manages oil prices at the expense of giving away real estate to US shale producers. Lifting production cuts could trigger an oil price fall. But keeping cuts in place could prop up prices to the benefit of rivals such as the United States, boosting production as a result.

OPEC (without the +) member adherence to quotas has been uncharacteristically solid during the pandemic. The Saudi-Russia price war in April 2020 saw production surge through the group 25.1mmbpd quota to almost 28mmbpd. But since post-COVID cuts began in May, OPEC production has on average been below the reduced quota. In October, the combined output target for OPEC countries was 21.9 mmbpd, and actual volumes were 21.6 mmbpd (1.1% undersupply), the third consecutive month volumes were below the group target.

Collectively, OPEC+ is on track to shave off approximately 5.5 mmbpd of supply this year, offsetting a substantial chunk of the COVID related demand decline. The OPEC cuts were originally set to be unwound further in January 2021, adding another 2.0 mmbpd to global supply. But sustained depressed global oil demand led to widespread expectations OPEC would decide not to raise production just yet. It surprised the market with a penciled-in 0.5mmbpd production hike from January, albeit much lower than the initial plan. On a year-on-year basis, we currently project an incremental 4 mmbpd from OPEC collectively in 2021, with an additional 1 mmbpd increase from Russia. (Mark Taylor)

Morningstar

Morningstar