Introduction

PitchBook’s recent “An LP’s Guide to Manager Selection” offered a framework for private-market manager selection to allow investors to look beyond the sectors’ limited and opaque performance data. This framework consists of six P’s (and a bonus seventh) that are not dissimilar to Morningstar’s five fundamentals of fund investing: People, Process, Performance, Parent, and Price. Many accredited investors may not get the same level of access or disclosure as institutions, so this paper attempts to adapt the PitchBook framework for those examining evergreen, interval, and retail-oriented products.

Many private-market funds are offered in overlapping sequences of open and closed products. A fund of fund or feeder may access one or more of these products. Most marketing documents promote a track record based on prior offerings that are closed with all holdings liquidated, but these offer little in terms of predictability. This doesn’t change whether that’s the most, second-, or third-most recent. In fact, the most recent offering has the weakest predictability, as often some holdings are caused by estimated valuations, which move significantly in the last years of a fund’s life. The dispersion of category returns then is large between quartiles. With a greater level of opaqueness and with investments often being made before the portfolio is known, manager risk is exacerbated, especially with those offering a limited track record or an unfamiliar name. Like hedge funds, smaller, newer managers often provide outsize returns, but fear of the unknown causes many investors stick to a “brand name.” So, with a limited track record and recent fund performance being unpredictive, how should an investor approach the private markets?

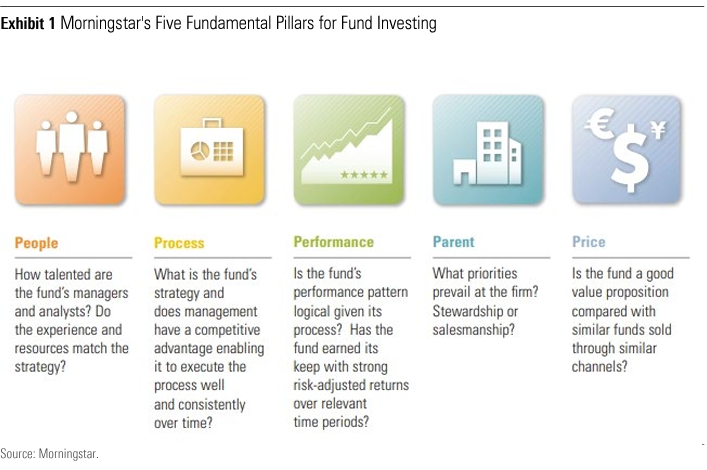

The Five Fundamentals of Fund Investing

In our broad categorization of alternative investments, most private-market offerings fall in our Modifiers grouping. In risk factor terms, this means many strategies contain the standard equity, rates, and credit factors but in modified form. Investors reduce the reliance on these factors and instead introduce complexity risk—the need for specific skills coupled with a complex investment that requires them—to generate value. An allocation may come from traditional asset classes and so, in reading this guide, many points of consideration may appear as extensions of those used in mutual fund assessments. Morningstar considers there are five fundamentals of fund investing: People, Process, Performance, Parent, and Price. These five P’s form the backbone of our manager ratings process where thinking about the whole picture can ensure that an investor has gone beyond a performance ranking to gain a better view of the overall capabilities of a manager. This is not an exhaustive list, and there are plenty of other frameworks, but it should be useful for teasing out potential red flags.

Fundamental One: People

The first P, People, looks at the overall quality of a strategy’s investment team—those who make the portfolio decisions. If there is more than one person in charge, it looks at how conflict is managed, and decisions are shared. It considers resource allocation within and in support of the team and the expertise and relevance of those resources. Smaller firms have a large overlap between the investment and management teams, but this is not the case for firms with multiple strategies on offer.,

- Composition—How is the team composed, both in roles and in its complementarity? Private-market firms are a well-trodden path for many recent MBAs after spending their formative years in similar investment banking roles. Groupthink is a risk. Does the manager have the collective capabilities to maximize the value of an investment through the structuring of a deal, the operation of a company, and the exiting of an investment—often in newer industries or markets different from their prior experience?

- Key-Person Risk—A long-term partnership is on the table here, so it needs to be bilateral. There must be comfort that the people they put their trust in will be there throughout the life of the fund. Many mutual fund products do not have the Key-Person Clause seen in direct investments, and an imbalance may exist on investment terms between investor segments or one large investor could affect all investors.

- Longevity—A new fund launching based on a partner’s long tenure in private-market investing needs the same succession-planning consideration as any mutual fund offering.

- Background Checks—Many portfolio managers are unknown, and relationship databases tracking the general partners running older funds are scarce. Realistically, this is hard to do unless an investment consulting firm has recommended a fund, but if employment histories seem vague, be concerned.

- Turnover—It is uncommon for teams to remain intact between capital raisings, and it may be unclear as to the contribution of individuals to any prior successes. New firms wait for asset growth before hiring, so a clear hiring plan should be in place to avoid overworking existing staff.

- Outsourcing—As with mutual fund managers, external research may be used to inform views, and other professionals may be engaged to perform fund-related functions. What is different is the other outside roles often performed by private-market portfolio managers—such as sitting on portfolio company board seats or bankruptcy workout committees. Clarity is required on the extent of such external commitments.

- Experience—Cumulative numbers can be misleading, with one older partner dominating or team members all having the same years of experience but only across one investment cycle. Firms tend to call any employment as experience, including periods when analysts may have no hands-on exposure to a fund or its assets. Time in the market and actual investment experience are two different things.

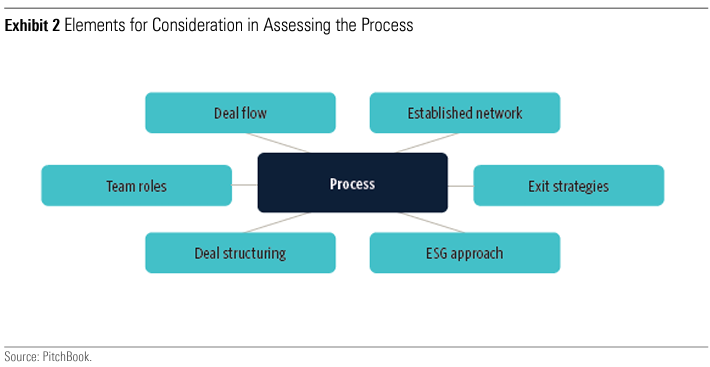

Fundamental Two: Process

Process is the end-to-end description of how deals are sourced and closed, managed, and profitably divested. Many private-market managers talk about their networks and deal-sourcing acumen but little about how they will then manage the portfolios and even less about the exit. A level of macro awareness is required, as holding a company slated for IPO or a loan to a cyclical company may be quickly affected by a change in macro scenario.

Selection and Sourcing

- Networks—Almost every manager claims proprietary deal flow, but can it be substantiated? While vertical or channel integration can be an aid, most deal sourcing is not done in a way that others cannot mimic. The same applies to networks—will it really generate enough quality deals to fill and support a fund, or is it more ad hoc and opportunistic?

- Decision-Making—This is an understanding of how, and by whom, each deal is decided. If decisions are made by committee, how is voting decided? Democracy can introduce tardiness, while limiting decisions to key executives can result in too great a distance between them and the proposed industries or sectors to realize the value proposition. Some firms pass the investment proposal docket along the line between those introducing, assessing, and managing the deal, while others seek continuity.

- Experience—Does the team have experience in structuring deals or in working out distressed holdings? The portfolio manager needs to bring more than just capital to the table. Is there any experience with diverse boards or working with other investors to achieve the best price for an asset?

- Depth—Extensive human capital is required along the value chain. Can the team really be experts from sourcing to managing to divesting? For funds with company holdings, can the individuals really adding value to a board, and how many boards can they bring that value to at once? Much like a stock portfolio, it is important to know that a manager has the capacity to be on top of every asset in a portfolio.

- ESG—If ESG is an investor utility, can material nonfinancial risks be understood and mitigated to create a more durable long-term business model?

Portfolio Construction

- Portfolio Diversity—How diverse will the offering be, and how long will it take to get there? Unlike for mutual funds, many managers are unaware of competitor positioning. Position sizing should be about more than the likely investment size and number of target companies in the portfolio.

- Portfolio Size—What is the target portfolio size? Whether it is loans, companies, or properties, this should logically connect to the capacity of each member of the investment team—not just in asset selection but also in ongoing management and divestment of the assets.

- Concentration—How much can be invested in one company/asset class/sector/issuer? These limits are often tested as a fund grows, so early investors are usually most at risk. The manager also has the temptation to get the ball rolling and generate returns, bringing an immediacy to capital deployment that may not align with that stated process.

- Specialisms—Is the fund a specialist or generalist? Those specializing can be hit by exogenous factors, such as supply chain disruptions, adverse regulatory or judicial decisions, or a massive firm utilizing tremendous resources to block potential disrupters, impacting the whole portfolio.

- Deployment—How quickly will the fund’s capital be invested? There is a fine line in the ramp-up of a fund: Too quickly may highlight a lack of selectivity, while too long could be too much model dependency. Knowing the indicative timeline can mean the managers can be held accountable.

Fundamental Three: Performance

As mentioned earlier, despite what some older studies suggest, the third P, performance, is not a predictor of future success. Within private markets, given the duration of the investments, it is very hard to ascribe any fully realized portfolio to the exact team, philosophy, and process currently being promoted. A portfolio manager with 15 years’ experience may only have had a glancing impact on the portfolio in her first role. A manager taking credit for a deal that occurred within a completely different infrastructure should be met with skepticism. So, what is needed?

- Direct Performance Attribution—There should be clarity on existing deals completed by the current team at the current firm. New managers may come to market with a couple of deals funded by seed investors to show proof of concept. They should be able to discuss how the team sourced these deals,

- how they are progressing, and how its actions have affected this progression. While exits from these deals may be years away, the team must show it has the expertise and network to affect the outcome.

- Prior (External) Fund Performance—If the team was intact during the life span of another fund, the conversation is the same as that of a boutique spinning out of an asset manager. What has changed between that fund and this? What the manager cites as impediments may have been necessary guardrails for investors that are now no longer in place.

- Case Studies—For a completely new manager bringing together a new team in a new firm, evaluation is even harder. Are investors providing money for this manager to learn with? While an energetic and knowledgeable portfolio manager may offer gravitas, with private markets, a much broader contribution is required, and investors should be on guard against any individual overstating their contribution.

- Valuations—Valuation methodology should be an explicit conversation, especially in relation to the prior portfolios being held up as evidence of skill with separate evaluations of realized and unrealized assets.

- Return Composition—There must be a clear articulation as to the future composition of returns. Private markets are more than just buying, improving (valuation or operationally), and selling. Unless it is venture capitll, one or two outsize returns shouldn’t drive performance.

Fundamental Four: Parent

The fourth P, Parent, includes everything about a firm: why it exists, who owns it, how firm-level decisions are made, and so on. Although some of the other P’s offer greater impact, a strategy is not durable without backing from the parent. The firm’s management sets the tone for an evaluation including capacity management, risk management, recruitment, and retention of talent, as well as firmwide policies that align the firm’s interests with those of its investors. Morningstar prefers firms that have a culture of stewardship that are not heavily weighted to salesmanship. These tend to operate within their circle of competence, do a good job of aligning interests, and treat investors’ capital as if it were their own, while firms oriented to prioritizing their own interests view investors as sales opportunities.

- Philosophy—Often new firms are created by the general partners of a bigger firm seeking a greater share of the economics, a change in culture, or a choice of specialism. Although this may be better for the manager, does it benefit the investor? Does the jettisoning of perceived negatives overcome the differing support structures, business management responsibilities, and changed access to talent and deals? As many private-market firms are being gobbled up, at large valuations, by traditional asset managers, questions of autonomy and product development must be at the forefront of mind as these firms seek to generate a return on those acquisitions.

- Ownership—With new ownership comes questions of how the firm is managed. Compared with publicmarket operators, many private-market firms gloss over the details, often thinking that running an assetmanagement firm is about doing deals. If the same people are handling the investing, managing, fundraising, and investor-relations functions, they are perhaps spread too thin.

- Alignment—How well are the individuals managing the fund aligned with the performance experience of the investors? Both the upside and downside need to be shared. This tends to be more asymmetric with private-market firms. Any form of carried interest incentives must align with maximizing investment performance for both investors and the firm.

- Skin in the Game—For newer managers, if the team does not have the financial resources to collectively commit to a material percentage of the fund size, the team members should be willing to prove that what is being committed is a significant personal stake. While it may be uncomfortable, managers are asking investors to tie up capital should be prepared to answer how they are aligned with their partners.

- Competitive Advantage—Like any fund manager, they must bring more than a checkbook. A competitive advantage must exist as both a fund manager for investors and as a capital partner for potential portfolio investments. Claimed specialisms may just be their view of their talents.

Fundamental Five: Price

Noninstitutional private-market investors have limited pricing power. New product launches tend to anchor themselves to competitors’ pricing models on the assumption that this is what the market will bear. This type of approach was witnessed with hedge funds, inhibiting broad adoption. Within offerings for accredited investors, we do see more nuance. Private-debt offerings converge around similar price points, as does venture capital and real estate. PitchBook noted in a 2020 report that emerging managers, just like any fledgling business, should try to be more investor-friendly to get their firms off the ground. The issue for many is they must partner with third-party distributors, and with an extra mouth to feed, even matching large firms with in-house distribution teams is a stretch. This isn’t dissimilar to taking on an anchor investor in exchange for a reduced management fee—the deal must not be so advantageous to the outside investor that the firm cannot run its business.

- Some managers may feel that higher fees are acceptable if the expected returns are better than cheaper options. Others figure a bird in the hand—or a lower fee for the life of a fund—is better than two in the bush—or potential gains from this long-term investment. PitchBook data shows that more than half of private-market funds charge less than 2% for their management fees—this is at the institutional level, so before any periodic liquidity structures are formed, or capital introduction fees are paid.

- In private equity, there is often a hurdle rate at around 8% or so before performance fees are paid. This may have had some flexibility when interest rates were at record lows, but now that rates have risen, investors should not have to accept anything less.

- In a similar vein to the bad old days of hedge funds, there are a myriad of fund expenses that are apportioned in a manner to that seen with public-market investments. The Securities and Exchange Commission is seeking to rectify this and has in 2023 set rules for funds to disclose in greater detail their quarterly fees and expenses to investors. There will also be greater restrictions on allowing favored investors the opportunity to exit on easier terms than others.

Summary

Many private-market companies only operate in the institutional realm. The media tends to highlight only the largest managers, while hundreds more concurrently raising capital cannot attract this sort of attention. Many of these are specialist firms offered by distributors that only focus on private markets. As products are increasingly being marketed to accredited, or wholesale, investors, this is being done by distributors that, again, may not be well known to investors. Many are themselves new to private markets and not related to, or in day-to-day contact with, the actual asset manager. Finding smaller newer managers, or a sector specialist, and not settling for one of the behemoths requires increased diligence. Turning to investment consultants and research houses brings exposure to more managers and a deeper sense of the marketplace. These, too, have capacity limitations, and in many instances, the depth of experience runs dry very quickly in assessing what are new investments to most. Clarity around their processes, assessments, and recommendations is key, rather than blind acceptance of outcomes.

The 5 P’s provide a framework to help organize areas of focus for a potential investment. This framework is not prescriptive, and if there was only one way to run a fund, then the investment industry would be very boring. Ultimately, investors must do their own due diligence. While seeing a name in the media, in the holdings of pension funds, or with a fund rating may provide reassurance, remember that both Bernie Madoff and FTX successfully raised capital because of such a halo effect. Buying a brand name doesn’t alleviate this onus. If this all seems too much, question why private markets are required in your portfolio in the first place to meet your investment goals.

Morningstar

Morningstar